Castle Peak Mine – Mining Lot No 12

Tymon Mellor: Development of a modern mine at Castle Peak to extract Wolframite or Tungsten ore was awaited with much anticipation by the Colonial Government, but following a number of failed ventures and after much illicit mining, nothing came to pass. Mining Lot No. 12 was returned to Government and the area absorbed into the Ha Tsuen/Castle Peak Firing Range.

Early Workings

Mining at Castle Peak was first recorded in the 1918 Report on the New Territories with mention of “the demand for metals led to much prospecting, and to two new mining ventures for wolfram, one at the junction with the Southern District near Shing Mun, and one near Castle Peak”. It is likely that local farmers discovered the mineral veins in the streams and started excavating the ore, leading others to join in.

In pre-war Asia, Marsman was a large mining and civil engineering company based in Manila. It operated mines in the Philippines and wanted to work in Hong Kong. In the summer of 1936 it was invited to look for mining opportunities in the Colony by a Mr Hull (not sure who he is). Marsman would later build the Air Raid Precaution tunnel network in Hong Kong which was mired in a complex corruption case in 1941 over the cost of the works.

In a letter dated 23rd September, 1936, Mr G H Newman, a geologist for Marsman Investment Limited, reported its findings. Marsman had undertaken a preliminary review of a number of mining opportunities in Hong Kong. This included Lin Ma Hang, Ma On Shan, Silver Mine Bay and Castle Peak. Under the latter, Mr Newman recorded; “This area includes the old wolfram mines located on the slopes of the Castle Peak Range near Sui Hang, Sai Shan and Nam Long. This range deserves further prospecting”. A map and a request for a prospecting licence for the area was attached to the letter (but which is no longer in the current file of the Public Records Office).

The request for a prospecting licence was not fully processed by the Government, starting a chain of documentation mishaps that would ultimately doom the project. An informal prospecting licence was provided in the form of a letter. In the confusion, no one in Government mentioned the need for a prospecting fee or conditions to operate under.

Time of the Marsman

The prospecting was successful. Following an application for a mining licence, on the 16th May, 1941 the Governor in Council approved the issuance of a 21 year mining licence for Mining Lot No. 12. This covered the eastern slopes of Castle Peak, an area of 491 acres. What had not been identified by the Lands Office was the fact that the mining area included Lot No. 1724 of DD132, a private piece of land running along the bottom of the slope.

With the lease in place, Marsman Hongkong China Ltd using the existing access road, erected buildings, installed machinery and procured plant to commence mining operations. However, as noted in its letter of the 29th January, 1951, “The incidence of war concluded all operations, and it has not been possible until now to consider the question of reopening”.

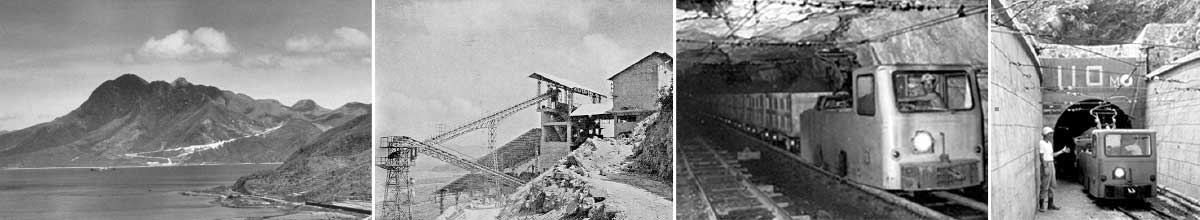

During the Second World War, the Japanese may have taken advantage of the new plant and undertaken mining activities. A review of the 1945 and 1949 aerial photos of the area shows extensive open cast mining operations and the buildings erected prior to the war. The exact nature of the buildings is not known but we can make a judgement based on their arrangement. A large area was cleared and a flat area was provided for a large building. This is most likely the offices, stores and plant yard. To the left (as drawn) is a building on its own, with road access. This is likely to be the magazine or explosives store, isolated to minimise damage in the potential event of an explosion. In front of the main clearing is a building, likely to be the coolie lines or labour quarters. The building to the left of the main site is probably the start of mineral processing buildings. The small building beyond the labour quarters is either the detonator store or a generator building.

The mineral deposits are found in a series of parallel quartz veins running along the hillside. They contain wolframite, molybdenum and they were expecting to find Bismuth. The mining approach planned to be adopted by Marsman is not known but the practice of the time was, at a low level excavate adits into the hillside to locate the mineral veins, then mine towards the surface, allowing the ore to fall under gravity for removal. Such an approach was adopted at Needle Hill and Lin Ma Hang.

Following the war, Marsman were ready to re-mobilise but were reluctant as they still had not yet received the lease for the land. The mining lease was found by May, 1951 in the Lands Office, and it had been signed and chopped by both parties but not issued. There were other problems as identified in the Registrar General’s memo of the 23rd July, 1951, these being:

– the date for commencement on the lease had been left blank and there were no records to indicate what had been agreed. A date of the 1st January, 1941 was suggested;

– it was not clear if boundary post and survey fees had been paid;

– it was not clear if the earlier prospecting fee had been paid; and

– according to minutes in the Lands Office file, Lot No. 1724 of DD132 was not Crown Land but was privately held, although it had been included in the mining licence.

Furthermore, the Director of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry requested additional provisions to protect existing forests and water supplies.

By the late summer of 1951, it was noticed that the Governor had not signed Marsman’s copy of the lease. Furthermore, illicit miners were active within the mining lot, and their approach to extracting wolframite was polluting the local water supplies.

In early 1952, the Commissioner of Labour had reviewed the situation and had a plan to address the problems. With regard to the payments, Marsman had bank receipts for the payment of the land survey, the Stamp Duty and $52 rent. The latter was assumed to cover the erected buildings in accordance with the lease requirements. As for the lack of a signature, this was put down to confusion relating to the transition of Governor Geoffry Northcote retiring and Sir Mark Young the new appointment. This was duly addressed.

In 1952, the Government was preparing a new set of mining lease conditions, and these would centralise the administration of mining in the hands of the Superintendent of Mines. The Commissioner of Labour gained informal agreement from Marsman that the new lease conditions would be issued but for matters such as rent, ores to be mined, royalties etc. the 1941 terms would be adopted.

On the 17th March, 1952 the agreed proposal was formally transmitted to Marsman along with direction that they should occupy the land immediately and control the illicit mining. Four days later, Marsman confirmed that the arrangement was acceptable but sought an understanding of what the new conditions would contain and clarification of payment of Crown Rent during the war years.

In May, 1952 a new problem arose. On the 1st December, 1950 the British Forces had gazetted a new tank firing range, Ha Tsuen Tank Range. It was not realised at the time that the range included land allocated to Mining Lot No 12. Given that the tank range would only be used between the 1st December to the 31st March, the British Forces requested mining be suspended during this period.

Clearly, this was not a practical solution, so a new proposal was presented; all buildings, magazines, tunnel entrances to the underground workings were to be located outside the boundary of the tank range. Given that all mining works would be from underground, none of the workers would be in the danger area. In June, 1952 the Superintendent of Mines wrote to Marsman requesting that they conform to this revised arrangement. They also wished Marsman to confirm that the War Department could in no way be held responsible for any casualties as a result of its activities. Marsman did not respond, as it had more fundamental problems to address.

During the summer of 1952 Marsman undertook a review of its Hong Kong business and decided to close down the operation. On the 26th September, 1952 it wrote to the Colonial Government to seek confirmation that it could transfer its mining interests at Needle Hill (Mining Lot No. 9) and Castle Peak (Mining Lot No. 12) to Messrs Hoong Foo Mining Co. Ltd. The Government had no objection to the transfer.

Needle Hill was eventually transferred to Yan Hing Mining Company Ltd on the 20th January, 1956 for HK230,000. However, Castle Peak remained with Marsman.

Illicit Mining

In July, 1952 the local villagers wrote to T G Strangeways, the Director of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry complaining that around 40-50 illegal miners were working the hills each day and polluting the irrigation water. Many of the workers came from the local village of Sun Wai Chai and following discussions with the village head, they stopped, but only to be replaced by miners from other villages.

Two forms of illicit mining were undertaken at the site, excavating the mineral from the veins, and, panning for the mineral within the soft top soil. The latter required the flushing of water to expose the heavy mineral, resulting in heavy sediment released in to the stream water. This made the water unsuitable for irrigating the fields and for drinking.

Typically, the illicit miners would work in small teams of three, excavating and panning the material. During a typical work day they would collect three catties or 1.8kg of wolframite ore along with small quantities of haematite, magnetite, molybdenum and quartz. These, they would sell on to a buyer each day for HK$10 a catty. The miners were making HK$10 a day each, compared to an average wage of HK$5-HK$6.5 for a semi-skilled worker or HK$3.5 to HK$5 for unskilled in 1952.

Despite the request for police assistance the situation on the hillside deteriorated. With the peak in mineral ore prices, villagers were now living on the hillside in the hits and the pre-war accommodation erected by Marsman. The illicit mining and water pollution continued to increase during the late summer of 1952. By November, 1952 Mr E B Teesdale, the D.C. N.T. was not a happy man; “I am very dissatisfied with the conditions on this Mining Lot where there has been widespread illegal mining since 1951”. He wanted the mining licensee to rectify the situation and restore the damage. Mr E B Teesdale was reminded by the Lands Officer that there was no obligation in the mining lease to restore damage caused by others, in particular damage that was compromising the future mining operation.

The hillside descended into “a complete shambles” as noted by T G Strangeways, until a police raid on the 17th October 1952, where 30 locals were arrested for illegal mining and brought before the Magistrate in Tai Po. Marsman also managed to clear the remaining free-lancers and implement security to the site.

Marsman had still not taken full possession of the mining lot. The only access to the hillside passed through agricultural land under Lot No. 1724, held by the Fung family. When in early 1952 Marsman tried to erect new offices and quarters, the road was blocked to prevent access and was advised that it had no right to pass over the private land. As can be seen in the figure above, the road and all the buildings were within the disputed lot.

An agreement had been reached with the Fung family before the war, whereby the family received 3 portions of paddy field plus some $4,000 per annum for a period of three years for the use of the road through its property and the land covered by Mining Lot No. 12. This agreement was no longer recognised by the Fung family and it now demanded a fee of HK$105,000 to be paid over a period of five years. Marsman considered the fee exorbitant and requested the District Officer at Ping Shan to arbitrate in the case. The Fung family refused to discuss the issue and the District Officer advised that he had no authority to resolve the issue.

In late 1953 it came to the notice of Marsman that the Fung family had sold or leased a portion of Lot No. 1724 to Vermicelly & Soy Products Factory for the operation of a new facility. The factory along with the Lot No. 1724 encroached into the Mining Lot No. 12 compromising Marsman’s rights over the land.

The Government was once more pushed in to a corner and by late 1955 was considering the option of re-entering the mining lot, the technical term for repossessing the site and cancelling the mining licence. The Registrar General paid a visit to the mining lot in December, 1955 to get an understanding of the situation. He reported his finding on the 28th December, 1955. He confirmed that the only access to the mining lot was through Lot No. 1724 in DD132. He noted that “we are now faced with a very unsatisfactory situation. The lessees cannot develop without access, and if we re-enter for non-development we shall be left with a Mining Lot no one will want”. He also requested confirmation that the vermicelli factory had been authorised.

By the summer of 1956 the Government’s options had narrowed, these being: Marsman to surrender the lease, re-enter and terminate the lease or if there was a confirmed mineral body, resume the private land to provide access.

In late 1954, Marsman commissioned Nippon Mining Co. Ltd. to prepare a study on how the mine should be developed, and also Nittetsu Mining Co. to study the extent and quality of the mineral ore. These reports were submitted in November, 1954, the key recommendation being to carry out a further seven months of prospecting to confirm the ore body. When the reports were eventually submitted to Government in June 1957, the Superintendent of Mines Mr J H Knapp concluded, “mining on the lot would not be profitable, and consequently Government would not be justified in resuming land to provide access for the licensee”.

Surrender

With discussion continuing on the best approach to take, in January 1958 “a new situation has now arisen”. The military wished to enlarge the Ha Tsuen/Castle Peak Firing Range, taking in most of the remaining Mining Lot No. 12. The range would only be used on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, and confirmation was required that this arrangement would not impact the operation of the mine. With the lease on the Mining Lot No. 12 expiring in just over three years, even if the deposits were workable, there would be little prospect of lease renewal as the military would object, and any further expenditure would therefore be wasted.

Without revealing the new military requirements, informal discussion commenced with Marsman on surrender of the mining lease. In a proposal to Government in a letter dated 18th August, 1958 Marsman was prepared to surrender the mining licence provided that the Government would in accordance with Clause 9 of the agreement, undertake “an impartial valuation of full and fair compensation by a surveyor appointed by H.M’s Government”. The company then noted a number of factors that had prevented them proceeding with the development:

– 44 months of military occupation from 1941 to 1945;

– delays in approvals as the District Office was focused on the new proposed airport development at Ping Shan;

– difficulties with private land incorporated within the mining lease and lack of access; and

– additional expenditure associated with clearing and maintain security from the “free-lance” miners.

By August 1959 a deal had been reached, Marsman would surrender the mining licence and Government would repay all the Crown Rent received, a sum of $17,414.49. Re-payment of the Crown Rent was approved at Finance Committee on the 6th January, 1961 and the lot was surrendered on the 27th January, 1960, some nineteen years after issuance of the licence without any legal mining taking place.

The Site Today

Today, the steep hill sides are covered with shrubs and bushes, and unless you look closely you may miss the signs of the previous mining activities, but they are still there. Take care if you go exploring as there are holes and poorly backfilled voids that could collapse. Along the hillside in roughly parallel lines, you can see where the mineral vein has been located and the ore extracted by the illicit miners. The working extends from the Leung King Estate to above Kwong Shan Tsuen, a distance of nearly 900m. Short headings, typically only a few metres long can be found in the bushes and by the sides of streams. This is where the miners have tried to locate the vein or to excavate the mineral ore from the soft material. Debris of broken rock can be seen on the hillside, and bands of quartz in the footpath.

The mineral vein is inclined at a 70 degree angle, and close to the stream crossings you can see how the excavation has followed the vein into the hillside.

All the buildings associated with the mine have been demolished as part of the Sui Lung Court development, although the base slab of the small building is visible by the side of the foot path.

With much of the excavation works occurring before the Pacific War, there are no records of production. How far the excavations extended no one knows and how much ore was recovered is also unknown. Marsman is still operating in the Philippines as the Marsman-Drysdale Group, focusing on the food industry, mining and property development.

As for Castle Peak, Marsman lost money on the venture, the Government failed to generate revenue, and a few hundred free-lance miners made enough cash to get them through the early 1950’s. Maybe that is testament to Hong Kong’s entrepreneurial culture.

Sources:

- Report on the New Territories for the Year, 1918

- NT “Black Gold” Rush Moves to Mountainside, China Mail, 7 August 1951

- Hong Kong Annual Report, 1952

- Public Records Office Files HKRS 58-1-182 (20), HKRS 58-1-190-11, HKRS 156-1-3014 and HKRS 265-11D-3019

- Lands Department, Mapping Service

This article was first posted on 3rd December 2017.

Related Indhhk articles:

- Marsman Hong Kong (China) Ltd – Needle Hill Tungsten Mine during 1938-1951?

- Jan Hendrik Marsman 1892-1956, connection to Needle Hill Tungsten Mine

- Jan Hendrik Marsman – Escape from HK during WW2

- Gordon Burnett Gifford Hull – Needle Hill Mine, Shing Mun Reservoir

- Kwong Shan Tsuen Mine – Castle Peak

- Castle Peak Pottery Kiln [青山陶窰] or Dragon Kiln [龍窰]) c1940-1982, Tuen Mun

- Castle Peak Ceramic Company, Tuen Mun 1927-1950s

- Unidentified Brickworks, (Castle Peak Ceramic Company?), Tuen Mun

- Q+A 26 Tsing Shan Mine (Castle Peak area)? – Japanese occupation, WW2

- Kei Lun Wai – Limonite Mine,Tuen Mun, and the Interim Mining Policy Committee