Mapping Hong Kong Part 10 – The 1963 Hunting Survey

Introduction

Tymon Mellor: With the completion and publication of the GSGS 3868 1:20,000 map of Hong Kong in 1928, the territory had a comprehensive map of the colony. As with any map, it was out of date the day it was published, and work commenced immediately on preparing new additions. However, wider problems were identified that raised doubt over the accuracy of the cartography.

Map Limitations

The process of establishing a survey network is as much about calculations as it is about the field work. One important area is the management of errors and how they are to be resolved. As a mechanical process, the measurement of angles and lengths is subject to errors. These are minimised through repetition and mirroring actions to average out inherent instrument limitations. With the development of a complex triangulation network, it is possible to identify and quantify errors within the system. These errors can then be distributed within the network to establish a ‘best fit’ solution.

This task was undertaken by the Geographical Section General Staff in London to resolve the varying quality of the survey information. The resulting survey station coordinates and triangulation network were published in 1930 for all to adopt[1].

GSGS Triangulation of Hong Kong (1930)

With the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the subsequent military campaign, the situation in the Mainland was deteriorating, and the defence of Hong Kong became an issue of concern.

In 1934 a review was undertaken into the defence of the territory, and the view was that the fighting would result in trench warfare, one assumes based on the recent experience of the Great War. Part of the review was to assess the need for updated mapping to provide for “large scale trench maps”. This would require the 1:20,000 maps “to be brought up to date, and enemy, as well as our own defensive organisation marked on it. This cannot possibly be done by hand, nor will it be possible to get it done outside Hong Kong”[2]. The experience from the Great War showed that there was the need for up-to-date maps of the battle fields showing trench lines and key features. Dedicated survey teams were used to prepare and maintain maps of 1:20,000, that could be issued to the troops. For the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, the Field Survey Battalion printed over 500,000 map sheets using its own local press. As noted by Lieutenant Colonel HSL Winterbotham:

“In the early days Field Survey Battalions had no printing machinery except hand presses. The Battle of the Somme taught us, however, that it was vital to be able to print at every Headquarters and to issue information a few hours after each successive advance. Every Field Survey Battalion was given two printing machines capable of turning out seven hundred copies or so per hour in one colour. These machines printed a map 35 by 22.5 inches. Once installed the difficulty was to allow them a minute’s rest. During operations they were always working round the clock, and any delay or hitch would result in a period of intense activity to catch up with lost time. The machines are cumbrous and very heavy. During the spring battles of 1918 we lost one, although we left it in an unworkable state, and we ourselves captured several German machines”[3].

A review of the PWD Survey Department by Winterbotham in 1930 had identified the need for the ability to locally publish maps, “There are few colonies now in which it [printing of maps] has not started….At the present moment there is no facility for printing official maps or plans in the whole of the Far East”[4]. In response, the Hong Kong Government prepared an estimate for the facility:

- $13,000 for a new building for the printer

- $13,000 for fitting out the building

- $10,000 staffing

- $13,500 for the printer

They concluded, “It is considered that the public demand would be insufficient to justify this expenditure at present”[5]. Even worse, given the poor financial condition of the Government due to the Great Depression, a report from the Retrenchment Commission (1931) had recommended the abolition of six out of the nine posts of European Surveyors. Things were only going to get worse!

As part of the mapping review, a comparison was made between the adjusted survey values with the original values, and differences of up to 4m were identified, with more extreme discrepancies of up to 7m and 12m in the case of Castle Peak[6]. Furthermore, it was apparent that the PWD had not adopted the new survey data but had continued to use its own values, and thus, two systems were in operation, therein confusing coordination and planning.

A subsequent post war review identified that the recorded angles were correct, but there were errors in the measured distances. The survey adopted a baseline between Partridge Hill and Channel Rock, a distance of 3,498m. Finding a suitable location for a baseline had proved problematic for Tate. The location needs to be clear of obstructions to provide a good line of sight and in a place that will allow repetition. Finding a site in 1924 was clearly a problem and adopting a line across water would have been a compromise as it would be impossible to physically measure the distance. The length between the points could only be established through trigonometric survey and it would appear that an error in the order of 8m was introduced. An error in the baseline would impact all subsequent calculations.

1924 Survey Base Line Partridge Hill to Channel Rock

The military considered that there was an urgent need for updated maps and maps to plan important military facilities, such as bunkers, defensive positions and trenches. In addition to the planning needs, the artillery required additional survey information to improve the accuracy of any defensive barrage.

With the recent construction by the military of the road from Diamond Hill to Shatin Pass, along with an upgraded Jat’s Incline, guns could be located on the ridge between Middle Hill, Temple Hill and Pipers Hill at the rear of Kowloon. These guns had a range of 16,000 yards (14.6km) bringing Tai Po into range, and to improve accuracy required the construction of observation posts, marking of key points, identification of potential targets along with other gunnery needs. Additional surveys would be required.

HMS Hermes and HMS Eagle

HMS Hermes, an aircraft carrier which periodically visited Hong Kong during early 1930s, deployed her aircraft to take aerial photographs for updating maps and to extend the survey north[7].

In 1934 HMS Eagle, an early aircraft carrier, was assigned to the China Station and unlike the HMS Pegasus, she had deck launched aircraft.

HMS Eagle in Hong Kong (1934)

Captain J D Newman of the GSGS arranged for the Eagle’s planes to survey Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon area. The new aerial images would allow the 1:20,000 to be updated and provide the military with the necessary information on the Kowloon hills.

It is understood that the survey of the island was completed by January, and of the Kowloon area in November 1934 based on contemporary correspondence. However, they do not match the respective dates indicated in NCAP.ORG.UK site of March 1934 and January 1935. The Hong Kong images captured the new catchwaters constructed as part of Aberdeen Reservoir and the preparatory works for the construction of Shing Mun Dam.

HMS Eagle Aerial Survey (1934)

Based on the new mapping information, the military authorities planned the Gin Drinker Line, a series of defensive positions along the hills of Kowloon as defence against a Japanese invasion. This included bunkers, observation posts and the Shing Mun Redoubt, all constructed by 1937[8].

Japanese Maps

Following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbour by the Japanese on the 7th December, 1941, the Japanese initiated the Pacific war. Three days later on the 10th December, 1941 following a scout survey, the Japanese army attacked the Shing Mun Redoubt, overwhelming the under resourced British troops and so paved the way for the assault on Kowloon and Hong Kong Island.

It was only slightly earlier on the 12th October 1941 that the Japanese army had been given the order to plan for the Hong Kong operation. The Koa Agency (Asian Development Organisation) a covert Japanese organisation based in Hong Kong, provided information for the Japanese military and was tasked along with the local triads with preventing the destruction of transport routes by the British ahead of the invasion[9].

Thus, where the Japanese army invaded on the 8th December, 1941 they were prepared, possessing detailed 1:25,000 maps of the territory showing roads, paths and contours. The map was annotated with notes about military positions and firing directions, along with other critical military information. The base map looks to have been taken from the 1930 GSGS 3868 but includes updates including buildings on Wanchai reclamation, Kai Tak control tower (1936) and Aberdeen Reservoir (1931).

Extract of Japanese Military Map (1939)

Post War Map

With the liberation of Hong Kong in August 1945 the need for new maps was high on the list of priorities. The GSGS updated the 1:20,000 series (GSGS 3868) with information from the 1930 surveys and new RAF aerial surveys from 1945, and issued the 2nd edition of the map in 1945. A third edition of the map was issued in 1949 reflecting the change in map grid and graticules (lines showing longitude and latitude). In 1952, a fourth edition was published for some of the sheets to reflect the rapidly changing environment on Hong Kong Island and Kowloon.

Following the re-occupation of Hong Kong, the RAF undertook a comprehensive aerial survey of the territory in 1945. They would regularly undertake aerial surveys of the territory with flights in 1948, 1949, 1954, 1956 and 1959, with a focus on the frontier areas and other military interests.

Lo Wu Railway Crossing and Sham Chun Hu (Jan 1948 NCAP)

In 1957, a new mapping series was published, the L8811 series, a set of maps at a scale of 1:25,000 published by the Director of Survey at the War Office, the successor to GSGS. The maps were a reduction of the GSGS 3868 series, updated with changes identified in the 1954 aerial images and field checks undertaken by the Royal Engineers in 1956.

In 1965, a new mapping programme was initiated when the Directorate of Overseas Surveys first published the L884 series in 1969. The new maps at 1:10,000 were developed from the December 1964 aerial survey and updated ground survey and survey coordination undertaken by the Hong Kong Government, Crown Lands and Survey Office. The L882 series at 1:25,000 was generated from the larger L884 map. This would be the last map to be produced by the British, with Hong Kong made responsible for all future map production.

PWD Makes A Map

With the end of the Pacific War, the population of the territory quickly rose from around 600,000 in August 1945 to 1.8 million by the end of 1947. There was urgent need for rehabilitation of the existing infrastructure and the construction of new facilities to house, employ and support the growing population. However, despite the political will, there was a shortage of skilled resources and of the maps necessary to implement the infrastructure programme. The PWD under the leadership of V Kenniff tried to rebuild the infrastructure, but there were many challenges:

“Many of the pre-war staff did not return to duty and further loss of staff was sustained by the tragic death of Mr S C Collins, Land Surveyor, which occurred on 1st January 1947, at the hands of bandits”[10].

Many of the survey records were lost during the Japanese occupation and Kenniff realised the importance of have a documented survey network for all the new construction works. Focus was placed on re-establishing the triangulation network of 69 stations. The new survey team visited 27 requiring 12 to be rebuilt along with all the secondary stations. The coordinates for the stations, published in 1930 by the GSGS were used to recompute their locations as rectangular coordinates with Victoria Peak as the zero origin. This new set of coordinates was published in 1948.

By 1948, the PWD Survey Section had a staff of 44 while the approved establishment was 72, the majority of the missing staff being qualified surveyors, along with 6 land surveyors and 7 assistants. Despite the shortage of experienced personnel, the Public Works Department was actively developing detailed maps of the territory. As reported in the 1963 HK Annual report:

“In the period between the two world wars, the military decided to produce a map using the new survey method of air photography. A Colonial Survey Section came to the Colony in 1924-5 and produced a triangulation on which a 1/20,000 map was based. This map was drawn on 24 sheets and was one of the first in the Empire to be produced by air survey methods. In addition the Crown Lands and Survey Office produced its own series of 200′ to I” and 50′ to I” sheets of the developed areas of the Colony at about this time. When the Colony was liberated in 1945, very little of the pre-war survey remained; the first task of the land surveyor’s not employed on land administration was to collect what data and plans they could find and reconstruct. By 1952 these problems of reconstruction had been largely overcome and attention turned to the question of the New Territories.”

It was now apparent to the Government that the original Newland cadastral survey from 1904 was insufficient for the new land administration requirements. Thus, a new survey of the New Territories was started in 1953, adopting a scale of 1:1,200. Progress was slow, and there was a world-wide shortage of qualified surveyors requiring local staff to be trained up for the work[11]. By 1962, over 72,000 acres of land in the more accessible parts of the New Territories, had been surveyed suitable for land registration, but they had no level information as the topographic survey was a slower process. The new maps were unsuitable for engineering purposes.

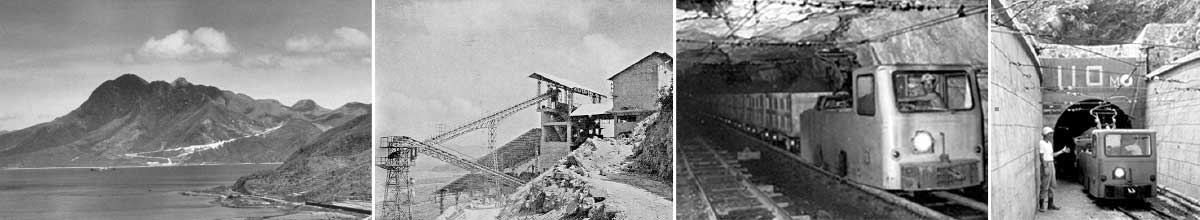

In 1962, representatives of an Australian firm visited the Colony and proposed undertaking an aerial survey of the territory. This prompted the Director of Public Works to invite tenders from specialist firms from England, Australia, Holland and the USA to undertake a territory wide aerial survey. The contract was awarded to Hunting Surveys Ltd of London for $6 million.

Under the Survey Production Manager H G Dawe on the 19th January 1963, a twin engine Cessna 310G chartered from Malaysia Air Charter arrived in the territory. Light turquoise in colour, the plane was flown by Singapore-born pilot A Gill and accommodated the camera operator Andrew McCully and A D M “Fergy” Fergusson, the expedition manager. Fergy, hunched over a periscope in the floor of the aircraft would give compass directions to the pilot and instruct the camera man when to commence photography[12].

Typically flying east-west, with the grain of the land, there were certain areas, such as the Shatin valley, over which the plane would fly in a different direction. The plane undertook 167 runs covering over 1,145 miles. After two hours of flying, the camera would exhaust the 200-foot film magazine, exposing all the nine inch negatives. On landing the film magazine was unloaded and passed to Gerry Mattingley who would develop and print the negatives in an RAF dark room at Kai Tak.

The goal was to photograph as much of the territory before the wet season, as Dawe noted “We look on every fine day as the last, and if you have lived in Britain you will see where we got the habit”. They were fortunate as the weather held, and they completed all the photography for the large-scale plans before the arrival of the summer rains.

Cessna Aircraft used by Messrs Hunting Survey (1964)

The scope of works for Hunting Surveys was to:

- provide capacity tables for the Shek Pik and Lower Shing Mun Reservoirs;

- provide plans at scale 1:600 with a vertical contour interval of 5 feet for areas not already covered by ground survey, a total of some 500 sheets;

- provide plans at a scale of 1:1,200 with a contour interval of 10 feet, for areas below the 600 foot contour and not already covered by ground survey. A total of some 1,300 sheets;

- supply 3 tellurometers;

- provide aerial photos of the land above the 600 ft. contour for future mapping, if required.

The Cessna aircraft was fitted with a Wild RC8 camera and planned to fly at a height of 2,700 feet for the 1:600 mapping and 3,900 feet for the 1:1200 maps. It was quickly discovered that this had to be varied to suit the elevation of the land and to provide suitable image overlap. A height of 7,000 and 8,000 feet was found to be more practical. Around 5,000 images were required to capture the territory[13].

Interior showing the Wild RC8 Camera

The three tellurometers were an early version of an electronic instrument for measuring distance. The tellurometer had only been developed a few years earlier in 1957 but it was the first instrument to directly measure distance. It transmitted microwave frequency radio waves and by receiving the reflected signal, it could be used to directly measure long distances. Over a distance of 20km, it had an accuracy of within a few centimetres, and could operate up to ranges of 70km. The unit came in a steel shock-mounted carrying case, 85 pounds or 38kg. Of this, the battery weighed nearly 13kg[14].

“Surveyors using a tellurometer, the latest type of electronic distance measuring equipment.” 1963 HK Annual Report

In advance of the aerial survey and other major projects, the main triangulation of the Colony was re-observed between October 1962 and February 1963 and the station coordinates re-calculated. To improve the accuracy and speed of the mathematical calculations, in 1965 an experiment was undertaken using an ICT55 electronic computer at the Commerce and Industry Department. The experiment demonstrated that the computer was of limited assistance and not suitable for routine survey work. An early desk top calculator proved to be much more suitable to the task[15].

The re-survey confirmed that original observed angles were good, but with the arrival of the tellurometer, the lengths between the stations were measured and errors were identified. To recompute all the survey information was a significant task and consideration was given to deferring the work until after the aerial survey to avoid possible delays. It was decided to re-compute the stations ahead of the survey and the team set about a “production line” process, completing the task in a few weeks.

The PWD would establish the ground control through the existing survey network and add additional stations to suit the needs of the aerial images. Two options were considered:

- pre-marking targets ahead of the survey that could be identified on the images, or

- coordinating features identified on the aerial images.

Following discussion, it was agreed that Hunting staff would mark up the plans where control points were required and the PWD surveyor would provide the necessary survey data. It was found that to achieve the necessary coordination, one square mile at a scale of 1:600 required around 12 control points, while a square mile at 1:1,200 only required 3 control points. Two surveyors with labourers would take five weeks to locate the points for the 1:600 areas and two weeks for the 1:1,200 areas.

“A cartographic assistant in the Crown Lands and Survey Office of the Public Works Department, revises an old map from photo-graphs taken during the recent aerial survey of the Colony” 1963 HK Annual Report

With the completion of the aerial photographs, the PWD established priorities for the survey reports and mapping. With extensive water rationing in effect, the first priority was to establish the capacity tables for the new Shek Pik and Lower Shing Mun reservoirs. Cross sections were developed at 20m intervals and using an Elliot 803 Electronic computer, capacity tables were produced for every foot of water retained. With little water in Tai Tam Intermediate and Kowloon Reservoirs, it was also possible to calculate similar capacity tables.

Elliott 893 Computer

For the mapping, the priority area was the Kowloon foothills from Lai Chi Kok in the west to Lei Yue Mun in the east. New developments were either planned or being undertaken for the area and large-scale maps were urgently needed. With the completion of the control survey in the Kowloon foothills, work commenced in the Island in Pok Fu Lam, and elsewhere, Sha Tin Valley followed by Kai Chung, Tsuen Wan and Tsing Yi Island.

Image of Hong Kong Central (1963)

The Hunting team drafted the maps in their London office and then sent to Hong Kong for checking. Each 1:600 map took a surveyor 18 days to check before the markup was returned to London for final drafting. Before printing, the final task was to add the place names and house numbers etc. This was undertaken by the PWD using a Photonymograph, an early version of a labelling machine!

Photonymograph Type PN4 For Map Symbols and Lettering

By 1968, the survey work was substantially complete and new maps were available for the territory while many Government departments were making use of the aerial photographic library. The development of computing power had improved and in 1966 the survey department invested in the Facit C1-13 hand operated calculators, one for every three-survey assistants. They also invested in an Anita table top electronic computer, “complete with female operator”[16]. It was found that she was able to check the work of thirty assistants. Computers were starting to become engineering tools.

Facit C1-13 Calculator and Anita Computer

The success of the 1963 aerial survey demonstrated that the civilian Government had the experience and technology to prepare, maintain and publish maps. Aerial surveys would continue on a regular basis, initially borrowing a camera from Hunting before procuring a camera and a dedicated plane in 1971[17]. The survey office would regularly update and re-issue the detailed maps as the territory developed, along with smaller scale maps. The process continues to this day.

Image Sources

Aerial Images from 1945 and 1963 are available from Lands Department at HKMS 2.0, https://www.hkmapservice.gov.hk/OneStopSystem/map-search

Aerial Images for the RAF surveys are available from the National Collection of Aerial Photography,

https://ncap.org.uk/browse/countries/hong-kong-sar

- Triangulation of Hong Kong and New Territories, 1930, FO 925 ↑

- Appreciation by the Geographic Section, General Staff, the War Office, of the survey situation in Hong Kong and the New Territories with reference to the requirements of the land defence of that colony, Jan 1934. WO 181/85 ↑

- Geographical Work with the Army in France, HSL Winterbotham, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 54, No. 1 Jul., 1919 ↑

- Report upon the survey department of Hong Kong, Brigadier H St J Winterbotham, 25 Apr 1930, C0129/521/1 ↑

- Letter W T Southorn, Officer Administering the Government to P Cunliffe-Lister, 23 Sep 1932, WO 181/80 ↑

- Appreciation by the Geographic Section, General Staff, the War Office, of the survey situation in Hong Kong and the New Territories with reference to the requirements of the land defence of that colony, Jan 1934. WO 181/85 ↑

- Letter W T Southorn, Officer Administering the Government to P Cunliffe-Lister, 23 Sep 1932, WO 181/80 ↑

- Decoding the Enigma of the Fall of the Shing Mun Redoubt Using Line of Sight Analysis, Lawrence WC Lai, Stephen NG Davies, Ken ST Ching and Castor TZ Wong, The Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors, 2011 ↑

- Japanese Intelligence in WWII: Successes and Failures, Ken Kotani, 2009 ↑

- Report of the Director of Public Works For the Year 1946-47 ↑

- Air Survey in Hong Kong, A R Giles, Engineering Society of Hong Kong, 1964 ↑

- Mapping of Hongkong by Air, John Dyson, SCMP, 17 Feb 1963 ↑

- Air Survey in Hong Kong, A R Giles, Engineering Society of Hong Kong, 1964 ↑

- Tellurometer Manual, 1961 https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=MnRe0O4O4loC&pg=PA38&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false ↑

- Annual Departmental Reports 1964-65, Director of Public Works ↑

- annual Departmental Report 1965-66, Director of Public Works ↑

- Aerial Photography & Aerial Survey in Hong Kong, Gordon Andreassend https://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/hongkongairsurvey.htm ↑

This article was first posted on 12th August 2024.

Related Indhhk articles:

- Mapping Hong Kong Part 1 – Where Are We?

- Mapping of Hong Kong Part 2 – 1841 The Belcher Map

- Mapping of Hong Kong Part 3 – 1845 The Collinson Map

- Mapping Hong Kong Part 4 – 1866 Map of San On District

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 5 – Mapping Kowloon

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 6 – 1901 The Tate Map

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 7 – 1904 The Maps of King and Newland

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 8 – HMS Pegasus

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 9 – The GSGS 3868 Map