Mapping Hong Kong Part 4 – 1866 Map of San On District

Tymon Mellor: The new colony of Hong Kong was built on a Christian background with arrival of the western military and merchants. The territory became a base for missionaries who provided schooling, hospitals and religious services and the opportunity to spread the word into China. One of these missionaries was a young Italian priest, Simeone Volonteri who from 1862 would spend four years travelling around southern China, drafting a map from observations made during his experience. This would become the first westerners’ map of the area, the first bilingual map and the map used in subsequent discussion on the acquisition of the New Territories in 1898.

A Christian Town

Prior to the establishment of Hong Kong, missionary activity in southern China was limited to Canton, and only for parts of the year. The rest of the time, missionaries retreated to Portuguese-controlled Macau, a Catholic stronghold that was not especially amenable to Protestant proselytising.

With the acquisition of Hong Kong in 1841, the church had an opportunity to establish itself. Construction of the first church, for the Roman Catholics, was started in June 1842 with a Baptist chapel opening in July 1842. Regular Church of England services commenced in the autumn of 1842 and after some delay, the first stone of the St John’s Cathedral was set in March 1847 and the building was completed in 1849[1].

Hong Kong took a much more liberal attitude towards faith, accommodating the local Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, Sikhism (associated with the Indian forces) along with Christianity and Judaism practised by the early settlers. There were no restrictions on what kinds of religions could operate in the new colony.

Along with the Protestants, the Catholic Church established a foothold in Hong Kong when Swiss priest Theodore Joset established a parish in 1842. The following year, he built a church at the corner of Pottinger Street and Wellington Street. This drew in several Catholics from Macau, whose economy had been in decline for years. Eventually, the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built further up the hill in 1888; where it still stands today.

In 1842, American-born Baptist missionary Henrietta Hall Shuck helped set up Hong Kong’s first school for Chinese girls, and in the same year, British missionary William Lockhart established a hospital on Morrison Hill that was open to both Europeans and Chinese[2].

In 1860, the treaties ending the second opium war opened China to missionary activity. Protestant missionary activity exploded during the next few decades. From 50 missionaries in China in 1860, the number grew to 2,500 (counting wives and children) by 1900. The majority of the missionaries were British with around 1,400 personnel, along with 1,000 Americans, and with 100 personnel from continental Europe, mostly from Scandinavia[3].

Mgr Volonteri

One of the early missionaries was Monsignor Simeone Volonteri, an Italian priest. He was born in Milan on 6th June 1831 and he joined the church in 1855. He was ordained as a priest in 1857, at the age of 26. Leaving Italy on 15th September 1859 he reached Hong Kong on 7th February 1860 where he joined the Mission of the Propaganda of the Roman Catholic Church.

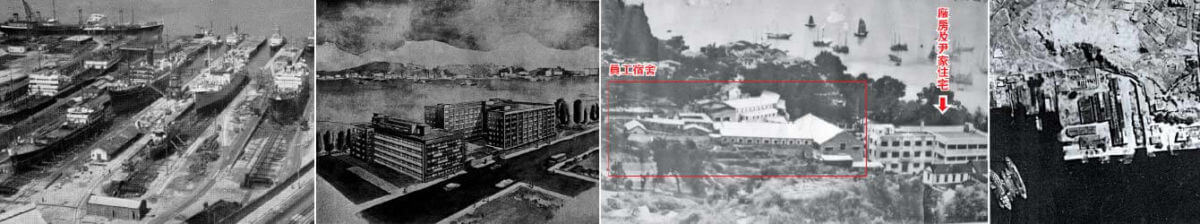

Mgr Volonteri suffered bouts of illness and in late 1860, he moved to Aberdeen, possibly hoping for better living conditions and was advised to get more exercise. Some two years later, he got the chance to settle and open a school in the mainland district of Bao’an County (then called San On), first, then in Wun ou (Tai Po) proselytizing to the kiln workers before moving north to Tai Wo (now Liuyue in Yuanshan) where he worked alone in the mission.

One day he asked a worker to enlarge the window on his house, and on the same day a baby died and a village woman felt sick. The superstitious villagers believed that Mgr Volonteri’s actions were responsible for this calamity and he was asked to leave[4]. He ended up in Ting Kok (Tai Po) where he established a school, which opened in April 1864 along-side a mission station.

Known to the locals as Padre Ho, a name derived from the transliteration in the local dialect of the first syllable of his surname, Mgr Volonteri was a well-liked priest among the Hakka rice farmers in the district. It would seem that the Hakka community was more receptive to the Christian message than the wealthier Cantonese, and it was probably safer staying in the hillier areas with the Tai Ping Rebellion (1850-66) raging in the major cities. He was accompanied on his trips by a local interpreter Don Andrea Maria Liang[5] and was often assisted by Father Andew Leong[6].

His missionary zeal took him throughout the district allowing him to make notes on the places he visited that he could use for the preparation of his map. At the time, collecting this information was illegal without the approval of the Emperor and it would have been considered espionage if known to the Qing officials. It was not easy work, as he described in a call for subscriptions to fund the map publication in 1866:

“The Map is the result of four years’ labor, and is made entirely from the personal observations of the author. The dangers, the difficulties, and the hardships which the work has involved, have been very great. The district is excessively mountainous and as occular demonstration had exclusively in all cases to be relied on, by reason of the worthlessness of native information, the fatigue attending travel has been no light matter. The villagers entertain the idea that their mountains contain auriferous deposits, and are very jealous of foreigners examining them. The consequence is that there is much difficulty in procuring the services of guides and still more difficulty in obtaining correct information on any point. In fact the idea above alluded to proves a strong incentive to the conveyance of false information, and excites resistance to the progress of the traveller, besides creating great personal danger.”[7]

He set up in the area several Christian communities and was very successful in converting the communities to the Catholic faith. He had to deal with two recuring issues, providing security from pirates and resolving tax issues from oppressive land owners. The presence of the church seemed to deter the pirates[8] but dealing with tax issues was more problematic.

In late 1869 Volonteri was working in Sai Kung, an area owned by the Liu clan of Sheung Shui, as tenant farmers the local villagers were required to pay tax to the Lius, but they believed the value to be oppressive and an exploitation. Volonteri helped form opposition to the payment through the organisation of self-defense armed groups to resist the big clans. However, during the crusade against the Sheung Shui tribe, some villagers were killed[9].

Following the incident Volonteri was transferred to Henan Province in February 1870 where he was appointed pro-vicar apostolic. He did well in his new position and was ordained bishop on 22 February 1874 and in 1882 was made Vicar Apostolic of southern Henan, China. He was well liked and became one of the oldest missionaries in China when he died at the age of 73. His final day, like much of his life, was spent travelling to an out-station where he died in his sleep on the 21st December 1905[10] in Fengqiao, East Henan (probably Fenghua, Ningbo)[11].

During his life he is credited with two maps, the first and most important being the ‘Map of the San-on-District, (Kwangtung Province), essentially covering modern day Hong Kong and the New Territories. This important map, engraved in Leipzig and published in May 1886, is considered to be the first bilingual map of Hong Kong and was, at the time of publication, unprecedented in scope and accuracy. His second map, is a reduced and updated variant of the first, published in 1874[12] covering Hong Kong Island and southern Kowloon.

The Map

There are no records of how the map was created, but it is clear that Monsignor Volonteri had some help. It had been suggested that the outline and much of the topographic detail were based on the British charts. This idea would seem to have merit as the coast line and hill heights are a remarkable match. It is interesting to note that there are no hill heights indicated to the west which was outside the scope of the British chart coverage.

In 1845 Captain Richard Collinson, brother of Thomas, the RE responsible for the first survey of Hong Kong Island, was responsible for the coastal survey of China from Hong Kong to Chelang Point. The resulting chart (number 1962) was published in 1849. The chart is coincidental with the easter portion of Monsignor Volonteri’s map and has a similar coast line, coastal features and mountain heights. The map also includes longitudes and latitudes, matching the Collinson chart.

There are some differences, possibly reflecting copying errors or the use of different map editions, the examples provided in this article come from an 1861 edition (the third version of the chart).

Comparison of Volonteri Map (top) with Chart No 1962 (bottom)

With the coastal outline acquired from the British Charts, the majority of the topography and information would have been provided by Monsignor Volonteri, an incredible feat considering that it includes:

- 9 large market places

- 22 market places

- 864 named villages

- 18 unnamed villages

- 3 Mandarin Residences

- 9 churches

- 5 sizable pagodas

- 3 mines or quarries

To collect all the data in four years would require constant travelling to new places four days a week without a break, clearly not a realistic venture. The villages are likely to have been only a cluster of ten or so families back in the 1860s requiring a tremendous effort to capture such detailed information over an area or as noted in 1866[13]:

“The scope of this Map embraces an area of about Forty Five miles from North to South, and of about Sixty miles from East to West – that is to say the District of Sun-on whereof Nam-tao, is the departmental town. It is within the district of Sun-on that Hongkong and its dependencies stood prior to their cession, and the whole Coast line for many miles adjacent is under the jurisdiction of the Mandarin at Nam-tao”

Thus, he must have had access to local records or local assistance. It is possible that he compiled much of the information from other missionaries visiting the area or with the support of the local mandarins whose residences are indicated. What however is perhaps the greatest achievement is the accuracy. When overlayed with a modern map, the village locations are shown to be in the correct position, an incredible achievement given the limited resources and technology available.

Detail of the San On District Map

The map establishes the ground relief using a type of contour, more a representation rather than a definition of height. This relief would have been established from walking between the Hakka settlements in the district. No doubt he would have a compass to establish the direction of the valleys and the relative positions of each village. With a coast outline and the major hills drawn, he could then add the settlements, taking time to record both the English and Chinese names.

Villages In the San On District Map

The map included a number of churches, three on Hong Kong Island in central and Aberdeen and six in what was the mainland, at Tsuen Wan, Wun Yiu, Sai Kung and Tin Kok in the New Territories along with Liu Yue and Shuimenlou in the mainland. It has been notable that there are no churches in the western portion of the map, the suggestion is that there were fewer Hakka communities, the focus of the Catholic church.

The Churches Shown on the San On District Map

Three mines are identified, included a lead mine at what is now Lead Mine Pass in the New Territories, an iron mine near Laoshe and a limestone quarry near Sanxi Village both in the mainland.

The map also includes three Mandarin Residences, the local seat of power for the district and an important place for official communications and security. Given the high levels of piracy at the time, it may have been no coincidence that Lantau was not explored, as it may not have been safe.

Residences of the Mandarins (Red) Identified Mines (Blue) shown on the San On District Map

Reaction to the Map

It has been suggested that modesty dissuaded Volonteri from including his name on the map, leading to the conclusion that the source of the cartographer was unknown[14], but this was not the case. In May 1866 Volonteri placed an advert in the Government Gazette seeking funds for the printing of the map. He was seeking subscription for 120 copies at $5 a piece.

An item in the China Mail the following month, publicised the proposal and noted that the map would supply important information “for tracing pirates from the bays and creeks on the coast to their piratical villages, which are frequently situated inland and which are at present terra incognita to the crews of our gunboats.”[15]

The map was sent to Leipzig for engraving and publishing, with over 200 copies produced. At the time it was the only map of the area and was used by the British authorities as a primary geographical reference until after their lease of the New Territories and the Survey work on 1901. The Governor, Sir Henry Blake referred to the map in a telegram of February 1899, “the Missionary map of 1866” and used in subsequent discussions in March 1899 with the British Secretary of State for the Colonies[16].

A Second Map

In 1874 Volonteri published a second map covering Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, and it was similar in style to the 1866 map but supplemented with additional details.

The 1874 Map Of Hong Kong

A Chinese version of the San On District map was later published by Lingnan Shaoyan in 1894[17] with additional details from the original.

A German Map

Not to be outdone in the missionary map production, the Basel Mission, a Swiss based Lutheran society established in Hong Kong in 1847 was also undertaking missionary work in southern China. They produced their own map, similar in style and coverage to the Volonteri map but with additional information including extended scope northwards with additional information on rivers and villages, identification of more churches including in the Sai Kung area, and only the identification of major towns and villages.

Unfortunately, the map is not dated, but given the lack of railways and the indicated size of Victoria, it would seem to be from around 1870 to 1880.

Karte der zur Provinz Canton gehörigen Kreise Tun,Kon, Sin,on, und Kwui,sen einschliesslich der britischen Kolonie Hongkong. Ref BMA 98565

Next Up

The Volonteri map was a great success and was the key document for the following forty years. No doubt it provided much needed funds for the missionaries but with the lease of the New Territories in 1898, a new map was required. Or to be accurate, three new maps were required: a detailed map for military use; a map of the expanded colony for the Government; and, a cadastral map to record land ownership required for land taxation and the reference for all land issues in the New Territories.

Sources

- Europe in China, The History of Hongkong from the Beginning to the Year 1882, E J Eitel, 1895 ↑

- How did Christianity become so influential in Hong Kong, Christopher Dewolf, https://zolimacitymag.com/how-did-christianity-become-so-influential-in-hong-kong/ ↑

- Protestant missions in China, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protestant_missions_in_China ↑

- The History of Evangelization in Hong Kong, 2005 ↑

- The San On Map Of Mgr Volonteri, Ronald C Y Ng, RASHKB Vol 9 1969 ↑

- The History of Evangelization in Hong Kong, 2005 ↑

- The Hongkong Government Gazette, 26 May 1866 ↑

- Follow in the Missionary Footsteps, the Evolution of the Catholic Mission in Sai Kung, 1841-2000, Chi Wai Yuen ↑

- Follow in the Missionary Footsteps, the Evolution of the Catholic Mission in Sai Kung, 1841-2000, Chi Wai Yuen ↑

- Death of the Bishop of South Honan, SCMP, 27 Mar 1905 ↑

- https://archives.catholic.org.hk/In%20Memoriam/Clergy-Brother/PIME/VOLONTERI%20Simeone.pdf ↑

- Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, Volonteri, Simeone (安西满; June 6, 1831 – December 21, 1904), https://www.geographicus.com/P/ctgy&Category_Code=volonterisimeone ↑

- The Hongkong Government Gazette, 26 May 1866 ↑

- The San On Map Of Mgr Volonteri, Ronald C Y Ng, RASHKB Vol 9 1969 ↑

- The China Mail, 17 May 1866 ↑

- The San On Map of Mgr Volontieri, James Hayes, RASHKB Vol 10 1970 ↑

- https://kknews.cc/zh-cn/history/bx5gamn.html ↑

This article was first posted on 18th March 2024.

Related Indhhk articles: