Cheong Alum and the case of mass poisoning at the E-Sing bakery

This article was written by Christopher Munn, and first published in the Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography, edited by May Holdsworth and Christopher. The publisher, HK University Press, and author have kindly granted permission for it to be posted here.

Thanks also to Christopher for sending the first image of the E-Sing bakery. The second image was included in the original article.

Thanks to SCT for proofreading the retyped article.

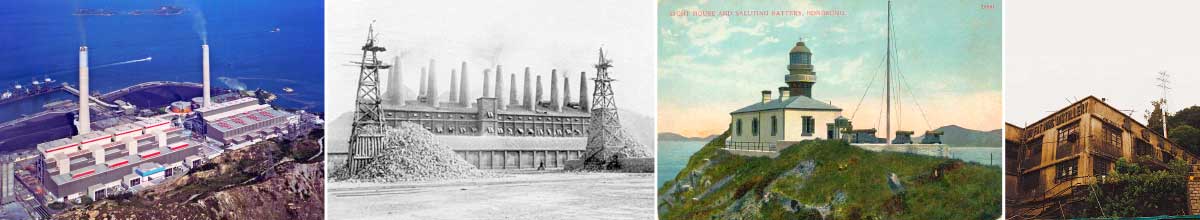

E-Sing bakery, date unknown

From an old but impoverished Xiangshan lineage, Cheong Alum gave up his studies at the age of 13 and moved to Macau, where he learnt how to do business with Westerners. He crossed over to Hong Kong at the age of 18, became fluent in English and served as a compradore to a succession of American and European employers, including Murrow, Stephenson and Co.

Having become wealthy, he established himself as a baker and general provisioner. He bought a biscuit-making machine from George Duddell, set up the E-Sing Bakery in Queen’s Road East, and became a supplier to the Royal Navy, the British Army and the colonial community. In 1856 he opened a branch in Canton, selling wines. liquors, beer and perfumery, in addition to the best bread and biscuit. By the end of that year, as anti-foreign disturbances spread during the early stages of the Second Opium War, E-Sing was the only large bakery left open in Hong Kong and the main supplier of bread to Europeans. On 15 January 1857 terrorists exploited E-Sing’s dominant position by lacing its morning batch of bread with arsenic in an attempt to murder the whole colonial community. About 400 people were poisoned; no one died immediately, but many fell ill with vomiting and great pain.

Cheong was an instant suspect, the more so since he had left for Macau early the same day with his family. He was arrested and brought back to Hong Kong. Many colonists, including W.T. Mercer, the Colonial Secretary, and Thomas Anstey, The Attorney General, called for execution without a proper trial. But the Governor, Sir John Bowring, whose family had been among the worst-affected by the poison, insisted that justice should take its course.

Examination of Cheong Alum, 1857.

Cheong was put on trial with his father, Cheong Wye Kong, and eight others before a jury of six Europeans on a charge of administering poison with intent to kill. The prosecutor, Anstey, failed to establish a link between Cheong and the crime, or a motive: the ‘flight’ from Hong Kong had been with the aim of sending his family back to their home country; Cheong himself intended to return to Hong Kong, and had only the day before purchased large quantities of flour; his children, who ate bread on board the steamer, were among the poisoned. Cheong and his co-defendants were found not guilty.

He was a tall, imposing looking man for a Chinese, and had been well educated. The respect and deference shown to him by all the prisoners were wonderful. On the Sundays, when I went to conduct a religious service with them, he quite took me under his patronage, had the books ready, and maintained perfect order amongst all who attended.

James Legge on Cheong Alum, in ‘The Colony of Hong Kong’, 1872

The acquital of Cheong has often been presented as a glorious moment in English justice. Yet this was not the end of the matter. Cheong, his co-defendants, and many others from the bakery remained in gaol on the Governor’s orders in appalling conditions while various suggestions – all of them involving banishment – were offered by community leaders.

Six months after his acquittal, with the approval of the Secretary of State, Cheong was released and allowed to leave the colony, with $2,000 taken in sureties against his returning within five years. Cheong moved back to Macau and opened a store selling Western goods. ‘He lived as if nothing had happened,’ according to a biography of him written in 1904 for the Cheong clan record. He arranged the construction in Macau of ships for the French in Indo-China and moved there permanently in 1862, establishing himself as a leading businessman and representative of the Chinese community; in 1879 he became Saigon chief of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Co. Much fêted by the French colonial administration and Qing officials, he died in Saigon at the age of 73 and his remains were taken by ship to his native village. He had seven wives, three daughters and ten sons, three of whom died in infancy.(1)

Source:

- Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography, ed M Holdsworth & C Munn, HKU Press, 2012 This wonderful book collects in one volume more than 500 specially commissioned entries on men and women from Hong Kong history.

See:

- Christopher has sent this article which he recommends and which was published online on 20th January 2015 after his Dictionary of HK Biography one:

Kate Lowe & Eugene McLaughlin (2015) ‘Caution! The Bread is Poisoned’: The Hong Kong Mass Poisoning of January 1857, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 43:2, 189-209.

http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/14522/1/Caution%21%20Revised%20article%20for%20JICH%2C%20August%202014.pdf

This article was first posted on 22nd February 2018.

Related Indhhk articles:

- Hong Kong bakeries around the time of WW2

- Three HK bakeries 1864 – Dorabjee Nowrojee’s, The Wanchi and The Colonial, and mention of two other companies

- Chun Hing Bakery, Biscuit & Confectionery Manufactory

- Ching Loong Bakery (正隆餅家) 1889 – 1963

- The Garden Company Ltd (嘉頓有限公司) founded in 1926

- The Lane Crawford Bakery, Stubbs Road, 1938-1948