Hemp – crop and craft, 1970 RASHKB article highlighting its disappearance in Hong Kong

James Hayes has kindly given permission for his short article about the production and use of hemp in Hong Kong to be posted on our website, though much of it is taken up with a description of this practice in China. The article was first published in the Royal Asiatic Society (HK Branch) Journal Vol 10, 1970.

For further information about the weaving of HK grown hemp into cloth during the annual visits of mostly male Hakka weavers please refer to the article, also by James Hayes, Itinerant Hakka Weavers in Hong Kong linked below.

Hemp by James Hayes

A few years ago, I wrote about itinerant Hakka craftsmen who came regularly to some of the New Territories villages to weave locally grown hemp-flax into cloth for making clothes (see the 1968 Journal, pp. 162 -165). In the course of reading and making further enquiries more information has become available that may interest readers of my earlier note on this now relatively obscure subject.

A few words of background may serve to show that the disappearance of this crop and this craft from Hong Kong in comparatively recent times signals the end of a practice that must have been followed from time immemorial in this region and elsewhere. Hemp constituted the main source of textiles in China until the introduction of cotton from the tenth or eleventh centuries A.D. According to M. Loewe’s Everyday Life in Early Imperial China (London, B.T. Batsford, Ltd., 1968), the planting of hemp for the coarse raiment in which most of the population was clothed was already one of the farmer’s main occupations in the Han time (202 B.C. – A.D. 200) along with another prime necessity, grain for food. Fragments of a short text on husbanding ascribed to Ts’ui Shih (C 100 – 170) set out a yearly programme of activities for the farmer and his household and include instructions on the cultivation and used of hemp. Unfortunately, however, despite the use of hemp clothing by the bulk of the Han population, it is of silk fabrics that most is known today. By the late Sung period in the mid 13th century, ordinary people still wore clothes made of hempen cloth since cotton, too, was a luxury though its use had begun to spread (see Jacques Gernet Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250 -1276 (London, George Allen and Unwin, 1962, p. 130).

The description of the planting, preparation and processing of hemp that follows is taken from (no date is given on the frontispiece but the contents date it to this period, see e.g. p. 60). It is the first I have come across that provides any detail, though E. Watson’s The Principal Articles of Chinese Commerce (Import and Export), published at the Inspectorate-General of Customs, Shanghai 1930, deals with the various types of Hemp and Ramie under the general head of Ma between pp. 50 – 59.

“Hemp, or, more properly speaking, fibres analogous to those of the plant which we know by that name, are extracted from several indigenous plants in China: these no doubt formed the first textile fabrics worn by the Chinese, as they did of other ancient civilized races. Since the introduction of cotton, however, the cultivation and manufacture of these fibres is limited to the finer sorts, called by the English grass-cloth. This is principally made from a plant belonging to the Urtica, or nettle family, named ma by the Chinese. In cultivating it, great care is taken in the selection of the seeds, and in preparing the soil. The former when gathered are packed in jars with sand or dry earth. A loose dry soil is selected; the ground is well ploughed, manured, and divided into beds, about eight yards long and one wide, whereon the seed is thrown broadcast, and earth is swept over it with a broom. Before it sprouts, a framework with matting is laid over the beds, to protect them from the fierce heat of the sun in June. When three inches high they are transplanted. Being perennial they are carefully tended during the winter and spring; and in the third or fourth year are ready for cutting. The plant is also propagated by roots, and yields three crops annually, the first in June, when the blades are comparatively short; but in a month or two they are seven or eight feet high, when the second cutting takes place. The latest crop is cut in September or October, from which the finest cloth is made; the first being inferior, coarse and hard. On being cut the leaves are soaked in water for an hour, and the fibre stripped by breaking in the middle; whilst the operator, generally a woman or a child, separates the filaments skilfully from one end to the other with the finger-nails. The next process is scraping the hemp with a knife by drawing the strips over the blade from within outwards, taking off all the mucilaginous parts; then it is rolled up into bundles, exposed for a day in the sun, then assorted, and the whitest selected for fine cloth. A partial bleaching is effected on the fibres before they undergo further division, sometimes by boiling, and at others by pounding on a plank with a mallet. When the cloth is finished it undergoes a process of glazing, which is done by a rude machine most effectually. A sort of bed or tray is laid down firmly in the ground, the inside curved or scalloped, and made very smooth. Upon this the cloth is carefully spread; a small cylinder is laid above, and upon that a stone with a smooth face, having the ends turned upwards. A man mounts this stone, and places one foot on each end, giving it a see-saw motion working the cylinder backwards and forwards with great power, and imparting a fine glaze to the cloth, equal to hot-pressing in European factories.”

It is not known to what part of China this description refers. For details of the plant species and practice in West China and Chekiang see A. Hosie, Three years in West China (London, George Philip and son, 2nd Edn., 1897) pp. 73 – 74.

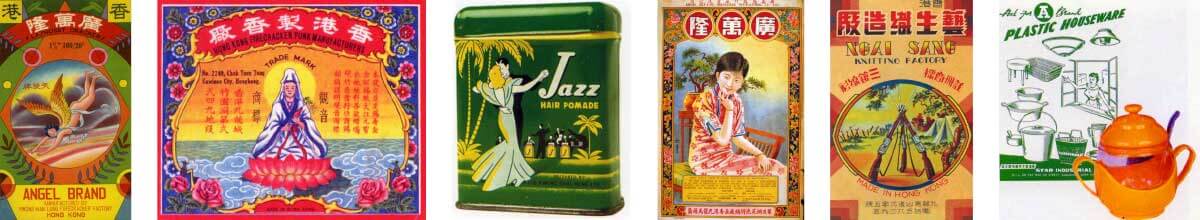

The image shown here did not accompany James Hayes’ original article.

Source: Hemp – Notes and Queries James Hayes, RASHKB Journal Vol 10, 1970

See: The Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Anyone with an interest in the history, art, literature and culture of China and Asia, with special reference to Hong Kong, will enjoy membership of the RASHK which is generally regarded as the leading society for the study of Hong Kong and South China.

This article was first posted on 24th September 2016.

Related Indhhk articles: