Sek Kong Airfield

Tymon Mellor: Originally known as the Pat Heung Aerodrome, work on the Sek Kong airfield commenced in 1935 with the construction of a road to the planned airfield. However, very little work was undertaken until 1950 when the British Government established a new defence strategy for Hong Kong requiring the mobilisation of an expanded military support. However, for some the airfield will be remembered as a detention camp for Vietnamese boat people and the riot resulting in 24 deaths.

The Need

Aviation landed in the territory in 1911 with the first flight by Charles Van den Born from the Shatin mud-flats and excitement grew with the development of aerial combat in the First World War. In early 1920 there was an enthusiastic gathering to listen to a speech by Sir A W Brown on how aviation was changing the world[i]. Every major city was building aerodromes, requiring at minimum an area of 300 acres for a new facility, but where would Hong Kong find a suitable site?

Through the failure of the Kai Tak Investment Company with their new garden estate development, the Hong Kong Government acquired the new reclamation underway in Kowloon Bay. The site was ideal for aviation and by 1924 an aviation school with a small grass strip had commenced operation. With the formal adoption of the site for an aerodrome in 1927, the Royal Air Force (RAF) established a camp on the site.

With growing civilian and military use, the aerodrome was reaching capacity and something had to be done. The British Air Ministry, the government body responsible for facilities for the RAF decided that a dedicated military facility was required while the colonial government established an expert committee to advise on the future development of the existing aerodrome.

Land Resumption

During secret discussions in 1935 between the colonial government and the Air Ministry, a site in the Pat Heung valley had been identified as being suitable for a new aerodrome[ii]. An area of 300 acres was identified around the village of Sek Kong (Shek Kong on the early maps) comprising of flat agriculture land and river.

The site comprised the resumption of 882 private lots amounting to 251.76 acres, along with 20 or so acres of Government land. Resumption of the site commenced in 1936, the largest exercise since the clearance for Shing Mun reservoir scheme in 1929. The process proceeded smoothly primarily due to the support from the village elder and the largest land owner, Mr Tang Pak Kau, with a final cost of HK$126,532. As noted by the J Barrow, the District Officer “The aerodrome site must surely be one of the most beautiful in the world”[iii].

Site Preparation

By chance, the government had been planning to upgrade the road from Au Tau to the village of Kam Tin, but with the new development, this was extended to support the new aerodrome site. In November, 1935 Public Works Department issued a tender to upgrade the existing track to 7.62m wide then extend it to Sek Kong[iv]. Work commenced on the 12 May, 1936 but was delayed by typhoons damaging the new bridges works, as noted; “construction proceeded unsatisfactorily”[v], and the road was finally completed in September, 1937[vi]. A month after the start in June, work commenced on the diversion of the river around the aerodrome site, and by the end of 1936, around 40,000m3 of material had been excavated and the channel was completed by the end of 1938[vii].

The river training works, along with the preparation of a suitable platform for the aerodrome required the mobilisation of hundreds of workers, resulting in a spike in the recorded malaria cases at the Kam Tin medical centre[viii]. With the construction of a road across the site, the area was ready for the next phase, construction of aircraft hangers during 1939 for occupation by the Fleet Air Arm. These were RAF pilots attached to cruisers and other warships who were being accommodated at Kai Tak[ix]. However, the war in Europe was more pressing for the funds[x] and no further development occurred.

Kam Tin Refugee Camp

In 1937 around 100,000 refugees arrived from Shanghai and northern China, escaping the Japanese fighting. The initial waves of refugees were accommodated in the urban areas but with the Japanese landing in Bias Bay in October, 1938 many thousands crossed into the territory in October and November.

With the fall of Canton in the summer of 1938, the government tried to limit the inflow by insisting that only those with $20 would be allowed to enter the colony. This failed to stem the flow. With nowhere to accommodate the people, the Sek Kong aerodrome was converted into a refugee camp. Matsheds were quickly erected on the site to hold 5,000 people. With the camp filling up, in November a second camp was erected south of Fanling using old railway freight cars for 3,000 – 4,000 people. With the completion of the Japanese offensive, many of the refugees were encouraged to return home. By the end of 1938 there were still around 3,000 people in the Sek Kong camp[xi].

Things deteriorated during 1939 as the war progressed with over 261,600 refugees in having to be accommodated. A third camp was opened at Gill’s Cutting (any idea where this is?).

Post War Paralysis

With the end of the Pacific War in September 1945, the territory started to look once more to the future. Kai Tak had been expanded by the Japanese but was considered unsuitable for the four engine bombers now in active service and alternative sites were being explored. In January 1947 the local RAF unit made enquiries as to the status of the Sek Kong site. Although the Air Ministry had refunded the cost of the land and site preparation works, the lease terms had never been agreed and the Air Ministry had no title[xii].

During the war, around 100 acres had been re-cultivated and a further 45 acres could be returned to farm use but over 130 acres were now barren and would need to be restored if the land was to return to farming[xiii]. The Lands Department were stressed about no one had been paying Crown Rent for the land and was seeking recompense from the RAF. However, after much discussion it was decided the money would be returned to the Air Ministry along with the difference in land valuation between acquisition and 1945[xiv] and the site returned to agriculture.

Defence of Hong Kong

In May 1949, the British cabinet was briefed by the Minister of Defence on a defence strategy for Hong Kong. The paper noted; “Hong Kong may well become the stage for a trial of strength between Communism and the Western Powers. If the Chinese Communist Government are able to force our withdrawal from the Colony, not only would the blow to our prestige throughout the world be irreparable, but the immediate repercussions in South-East Asia would add immeasurably to our defence burdens in that area”[xv]. The military assessment was that the mainland forces were not in a position to commit a large army to force withdrawal but the most realistic threats were:

- Internal unrest, probably sponsored by Communist inspired trade unions;

- large-scale influx of refugees in numbers beyond the capacity of the Colony to absorb; and

- sporadic attacks by Chinese guerrillas.

The proposal was to boost the existing military presence with additional resources and men, to make it clear that “we intend to defend Hong Kong against aggression”. The expanded force would be ready by September 1949 to defend against up to 40,000 Chinese Communist troops. With all the new resources mobilised; the territory would have:

| Army | 4 Brigades (9 battalions and 3 commandos) |

| 48 anti-tank guns | |

| 54 field guns | |

| 16 medium artillery guns | |

| 24 heavy AA guns | |

| 36 light AA guns | |

| 58 tanks (52 comets and 6 light tanks | |

| Air Force | 2 fighter squadrons (32 Spitfires) |

| 1 long range fighter squadron (16 Hornets) | |

| 1 flying boat squadron (5 Sunderlands) | |

| Flight control and early warning radar | |

| Navy (for whole of far east station) | 3 cruisers |

| 15 destroyers | |

| 1 light fleet carrier | |

| 1 replenishment carrier | |

| 1 hospital ship | |

| 24 local patrol craft for Hong Kong |

A New Life

Thus, in the summer of 1949 the Army were given a temporary permit to occupy the Sek Kong site and prepared for the area for the mobilisation of the new reinforcements. This included the construction of tent and nissen hut accommodation, a runway and parking areas. The latter were created using pierced steel planks, an American development for the rapid construction of runways and trafficked areas.

With the completion of basic infrastructure, the RAF mobilised on the site in January 1950 along with the Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force (HKAAF).

With the mobilisation of the new British reinforcements, a number of infrastructure projects were undertaken in the New Territories, and these include the construction of new camps, roads, fortifications and permanent facilities at Sek Kong.

In 1952 the road at the west end of the site was closed and the military area extended west with the provision of a permanent runway and support facilities.

RAF Transfer

In March 1978 the RAF base at Kai Tak was closed and the remaining RAF personnel and equipment were moved to Sek Kong[xvi]. However, the use of fixed wing aircraft was rapidly reducing as helicopters were more suited to the Hong Kong environment.

Detention Centre

With the fall of Saigon in 1975, 4,000 refugees fled and arrived in Hong Kong on a single boat. With nowhere to house the people, the Government organised a tented camp at Sek Kong until the refugees could be processed.

In the late 1980s the territory had a second influx of Vietnamese refugees arriving by boat, and after more than 18,000 had arrived in 1988 the HK Government announced that new arrivals would be sent to detention centres[xvii]. With the continuing arrival of refugees, it was announced in June, 1989 that a detention camp would be established for 7,000 people at Sek Kong[xviii], equivalent to ten days of arrivals. The new camp would utilise half the 820m long airstrip, with 100 tents provided by the Ministry of Defence in the UK. The loss of the runway would not impact the RAF who were operating helicopters, but would prevent the Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force from using their fixed wing planes and parachuting exercises had to be suspended.

There was much local opposition but the camp opened on the 21 June 1989 after the military had erected tents and constructed a secure compound. By July 1989 the camp was full, housing 7,200 refugees[xix].

The camp was not a happy place as conditions were “extremely unpleasant” with over 3000 people having been in the camps for more than three years. In August 1989, there was a mass breakout from Sek Kong[xx] resulting in the villages forming vigilante groups to patrol the area. With no end in sight to the problem, at the end of 1990 the tents were replaced with Nissan-type huts[xxi]. Things did not improve and on the 3 February 1992 there was a fire and riot that resulted in the deaths of 24 people and the trial of 34 men with nine being found guilty of rioting[xxii].

With a policy of returning the refugees back to Vietnam, the camps were slowly emptied and the Sek Kong detention centre was closed with the departure of the last 32 people in January 1993[xxiii].

Flying Clubs

In February 1972, following an incident in October 1971 at Kai Tak, where a HK Flying Club Chipmunk had an incident blocking the runway, it was decided the flying clubs could use Sek Kong “on a limited basis”. The Government had been reluctant to open the facility to private aircraft, notionally as there were no dedicated fire services but also because of the proximity of the Chinese airspace. However, given the congestion at Kai Tak, it would remove one more constraint[xxiv].

With the clearance of the detention centre and the reconstruction of the runway, Sek Kong was once more available for private planes.

Facility Upgrade

The Sek Kong airfield along with all the other military facilities were erected in haste using largely temporary construction. By the early 1960s it was apparent that the facilities would need to be maintained and a rebuilding programme commenced in 1961, replacing the Nissan huts and tents with reinforced concrete structures. At the same time a number of the facilities were renamed to reflect the regiments that occupied them. Thus, San Wai became Gallipoli and Norwegian Farm became Cassino, the names being derived from relevant battle honours[xxv].

Some of these facilities were once more renamed as they passed from British to Chinese occupation in June 1997.

The Sek Kong airfield was constructed to show a commitment to the territory by the British Government in a similar manner to the presence of the PLA Garrison.

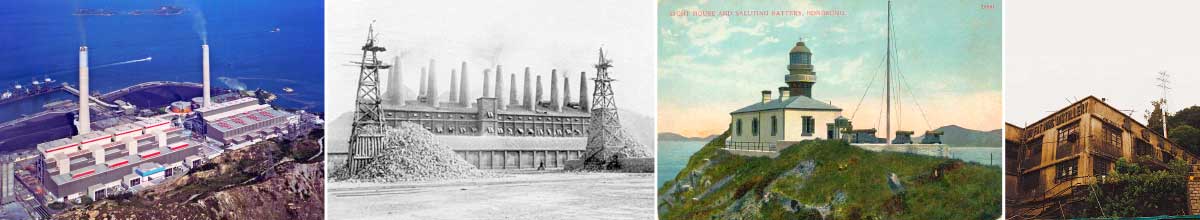

Images

John Holmes, Alamy Stock Photos, https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/?name=John+Holmes&pseudoid=3E13BDBD-84A8-4A4F-986D-0E36EA33818D

https://gwulo.com/photos-in-gallery?gallery=6110

Sources

[i] Aviation in Hongkong: Enthusiastic Gathering at City Hall, SCMP, 4 Feb 1920

[ii] Pat Heung Aerodrome, Letter from Government House, HK 2 Jan 1936, HKRS 156-1-1001-2

[iii] Report on the New Territories for the Year 1936, J Barrow District Officer, Northern District, 30 March 1937

[iv] Public Works Department Notice, 6 Nov 1935

[v] Report of the Director of Public Works for the Year 1936

[vi] Report of the Director of Public Works for the Year 1937

[vii] Report of the Director of Public Works for the Year 1938

[viii] Ambulance Reports, Activities During Last Year Reviewed, SCMP, 11 May 1937

[ix] Fleet Air Arm, Construction of Station in New Territories, SCMP, 4 Mar 1938

[x] File note, 14 Aug 1954, HKRS 156-1-1002-1

[xi] Annual Medical Report for the Year 1938

[xii] Summary of the Pat Heung Land, Sek Kong Airfield, HKRS 156-1-1002-1

[xiii] File note, 16 July 1947, Sek Kong Airfield, HKRS 156-1-1002-1

[xiv] Colonial Secretary, 27 Oct 1947, Sek Kong Airfield, HKRS 156-1-1002-1

[xv] Cabinet Paper, Defence of Hong Kong, 24 May 1949, National Archives, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7655703

[xvi] RAF Kai Tak base for auction?, SCMP 8 May 1977

[xvii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vietnamese_boat_people

[xviii] 7,000 Viets to be held at Sek Kong, SCMP 7 Jun 1989

[xix] Sek Kong detention camp full, SCMP, 15 Jul 1989

[xx] Bursting at the seams, SCMP 5 Aug 1989

[xxi] Sek Kong to shut down despite Kempster report, SCMP 11 Apr 1992

[xxii] Riot left camp like ‘battlefield’, SCMP 11 Jun 1994

[xxiii] Camp closes, SCMP 16 Jan 1993

[xxiv] Sek Kong for private planes, SCMP 3 Feb 1971

[xxv] Renaming of Army Camps, 5 May 1961 HKRS 156-1-1217

This article was first posted on 5th September 2022.

Related Indhhk articles: