Cha Kwo Ling Kaolin Mine

Tymon Mellor: To some, the workings at Cha Kwo Ling were not a mine as there was no shaft or entrance, but there was a large open excavation to remove a local occurrence of the mineral kaolin or ‘China Clay’. As one of the longest operating mines in Hong Kong, from 1928 to its closure in 1983 the mine had good years and bad but like many other mining operations in the territory, the Government’s changing policy and limited scale of the workings ultimately limited its potential and ultimately its commercial viability.

Introduction

Kaolin can be found all over the territory, a white clay that dries to a dust. Good kaolin clays were commercially worked at Lo Wu, Fanling, Tai Po, Pillar Point and Chek Lap Kok. However, the largest deposit was found at Cha Kwo Ling and proved to be extensive, high quality, producing around 80% of the local production.

The Site

The mine was located on the eastern shores of Kowloon Bay, between Laguna City and Yau Tong. The open excavation was located at the top of the hill with the material stores and support facilities at sea level, within the Cha Kwo Ling village.

The area was part of the “Four Hills of Kowloon” comprising of Ngau Tau Kok, Lei Yue Mun, Cha Kwo Ling and Sai Cho Wan where the Hakka villagers earned their living quarrying granite for use in the construction industry[i]. It is not recorded when stone quarrying started at these sites, but Lockhart’s 1898 report on the New Territories identified that there were monthly licence fees from quarrymen operating at Ngau Tau Kok, Lei Yue Mun, Cha Kwo Ling and Sai Cho Wan[ii]. Quarrying at Cha Kwo Ling was known to have started in the nineteenth century. The granite for the construction of the ‘Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus’ located in Yide Road, Guangzhou, completed in 1869 came from Cha Kwo Ling quarry. The building was also called the ‘Stone House’ because it was entirely made of granite[iii].

It was not until the late 1920s that an interest in the local clay became public and it soon became clear that the production of kaolin was more profitable than that of granite.

The Geology

When you walk around the hills of Hong Kong you can see the effects of the tropical rain and hot sunlight, how they have combined to expose and degrade the natural bedrock of granite, leaving behind its constituent minerals including clay, silicon and feldspar[iv]. This weathering can extend deep into the rock mass, following joints and weak zones. However, to get the quality kaolin the material needs to be hydrothermally altered as a result of granite intrusions. At Cha Kwo Ling, a 50m wide dyke about 300m long crossing the hillside has created the clay outcrop[v].

The white clay is found in layers, a few metres thick, flanked by granite to the sides and degraded granite and core-stones in between. The clay was originally found around 12m below the natural ground level[vi], requiring the removal of extensive overburden. The clay dries to a white power but varies in colour depending on the stage of decomposition from lighter to darker brown as a result of impurities within the kaolin.

Mining History

In 1923 the HK Government invited Dr R W Brock to undertake a geological survey of the colony. Assisted by Doctors Schofield, Uglow and Williams they began their field trips in September 1923 through to 1926[vii]. In 1926 W L Uglow published the first report identifying the key geological formations and mineral resources identified during the survey[viii]. He noted that the soils were products of rock decay and may be rich in potash, one of the basic constituents in fertiliser. He thought the territory would be an excellent location for soil research.

The first recorded reference to the exploitation of clay at Cha Kwo Ling was in August 1927 when Lo Yim Wing, I S Young, Sin Chau Li Ng and Chan Kwan submitted an application to the Government to obtain clay from the Crown Land[ix] at Cha Kwo Ling.

The application does not seem to have been endorsed, but it did initiate the Government’s calling for tenders for the site, providing a lease for the extraction of clay for 12 months. One of the more interesting lease conditions proposed by Government departments, but fortunately not included, was for the prohibition of export of the clay.

The advert was published in March 1928 in the local papers and six parties responded including members of the original 1927 application. The amount tendered for the licence varied from $60 to $1,050 with the proposed use varying from making sticks of chalk to porcelain and face powder. On the 4th May 1928 Mr Ho Chan Kwong was awarded the 12-month licence for his tender of $1,050.

Mr Kwong mobilised a team on site, constructing a new pier and laid a light railway line to move materials. However, before he could start serious work, the end of the 12 month licence was approaching, and so he requested a 12-month extension. However, by May 1929, Mr Kwong was still losing money on the venture and was no longer interested in maintaining the lease, so he removed the pier and railway line and the lease was advertised in June 1929 and in subsequent years as no one was able to make money on the mine.

As part of the ongoing geological mapping of the Territory, the Government undertook trials on different clays to see if they would be suitable for pottery. In December 1927, 14kg of kaolin was sent to the Imperial Institute in London, now part of Imperial College, London. They reported[x] that the unwashed clay had “only slightly plastic and having practically no binding power”, in other words it was useless. However, when the clay was washed, removing impurities of felspar and quartz the clay had a “fairly-good texture”, “worked well” and was much more plastic. It was concluded that good earthenware and even bone china could be made with the washed clay. This report may have encouraged more interest in mining clay.

In December 1931, the site was once more put out to tender but this time for three years, and twelve parties responded with tenders from $1,050 to $3,375. However, an additional tender was received from representatives of Mr George McBain and Co, described as “an old and influential Shanghai concern”. The offer was for a three-year lease with the option of an additional seven years of $4,000 per annum and $6,000 per annum for the extension. The proposal was attractive as it was based on adopting modern mining practices, spending $10,000 on plant and machinery. The proposal received support, “It is a good thing to obtain the interests of a Shanghai firm in Kowloon”, recorded Edwin Taylour. In January 1932, the proposal from McBain was endorsed and following some discussion of the finer points of the agreement the lease for Cha Kwo Ling Lot No. 1 was issued, dated 8th December 1931.

By 1933 three additional pieces of land had been rented for drying areas and for the construction of a chute between the upper and coastal workings. With the mine in production, the assets and lease were transferred to a locally registered company, Hong Kong Clays and Kaolin Co in July 1933.

By the end of 1933 after two years of a three-year agreement they had only shipped 1011.5T of product after paying $8,000 in rent and investing $15,000 in machinery. The quality of the clay had been found to be good but the market for the commodity was limited. In March 1934 the company was keen to proceed with the development of the mine but requested the lease be revised to a royalty basis instead of a flat rate.

Clay Shipments 1932 (ton) |

|||

Date |

Shanghai |

Japan |

Europe |

27/1 |

30 |

||

16/8 |

50 |

||

18/8 |

1? |

||

19/8 |

1.5 London |

||

13/9 |

48 |

||

1/10 |

1 Copenhagen |

||

4/10 |

40 |

||

19/10 |

85 |

||

20/10 |

85 |

||

7/11 |

30 |

||

7/14 |

100 |

||

Total (487.5) |

235 |

250 |

2.5 |

After some discussion the lease was revised in February 1936 from an annual payment of $4,000 to a quarterly payment of $1,000.

Production continued to improve but the company had stiff competition from the English China clay companies. In May 1938, with a view to renewal of the lease in mind, they enquired if a fee based on royalties would be acceptable based on 80 cents a ton for the first 2,500 tons a year then decreasing to 50 cents a ton up to 10,000 tons a year and rising to 53 cents at 15,000 tons. The Government were sceptical to this arrangement as to match the current $4,000 fee they would need an output of 7,500 tons, double the best production to date.

After much internal discussion and the release of the Kershaw report[xi] examining mining in the territory, the Government made a counter proposal in November 1938 based on a new ten-year mining lease commencing 1 January 1939. The general conditions for the new lease were agreed but it was not until February 1941 that that actual document for Mining Lot No. 11 Cha Kwo Ling was issued for review and approved by Exco on the 3rd April 1941.

As part of the Kershaw report, a visit was paid to the mine site and noting that twelve to thirty coolies were employed on a daily wage in a small-scale mining operation with an average output of 2,500 tons per year. It noted that “Although the mining is awkwardly situated and cramped for space, there is room for considerable improvement in the method of treatment and there is no doubt that a clay of a more refined quality could be produced which would have a wider market and fetch a relatively higher price.”

With the occupation of the territory by the Japanese during the Pacific war, work on the mine was suspended and the facility fell into disrepair. With the surrender of Japan in August 1945, it took some time to revive the company allowing mining to re-commence in 1946. The company had to rebuild the storage sheds and replace machinery and equipment removed during the war. However, with the lease running out in December 1948 they were reluctant to invest any more without security of tenure. After some delay, the Government agreed to extend the lease by four years to December 1952, reflecting the loss of production during the war[xii] and revised the royalty from $0.8 a ton to $6 a ton.

In the post war environment, the colonial government set up a trade deal with Japan allowing merchants to sell through government channels[xiii]. The HK Clay and Kaolin Co Ltd, took advantage of this scheme, selling 40 tons of kaolin a month, with the remainder being supplied to the local market.

In the early 1947, the Hsing Hwa Ceramic Company invested $400,000 to establish a ceramic factory at Castle Peak Road for the production of floor and wall tiles. By July the factory had employed some 300 workers but had no clay to fire. They had hoped to secure a supply from Cha Kwo Ling, but were told that the material was “subject of a contract made with the Hong Kong Government for delivery to Japan in exchange for Japanese goods” and there was insufficient left to provide the requested 40 tons per month.

Hsing Hwa, requested the Government to issue them a mining licence so that they could secure their own supply. In reality, this was a negotiating position as there was sufficient supply from Cha Kwo Ling, but Hsing Hwa wanted a lower cost. It would seem the situation was commercially resolved in September 1947 when McBain purchased the company for $250,000.

In 1948 the Government established a new committee to review the approach to mining and prospecting in the territory. One of the results was the formation of the Mines Sub-Department within the Labour Department in October 1951[xiv], to supervise and control mining operations within the territory. Within this climate, the mining lease for Cha Kwo Ling came to an end but there was reluctance by Government to renew while the review was ongoing. It was mutually agreed to continue the mine operation under the conditions of the expired agreement while the new agreement was finalised. By the summer of 1954 a new Mining Ordinance and Regulations were published providing mining leases up to 21 years, but there was no sign of a new licence for HK Clays and Kaolin Co, so they were concerned about the uncertainty of the situation[xv].

They had made significant investments in the mine and community, including the provision electric lights and clean water to the village and employing 50 to 60 of the villagers. In January, 1955 the Hong Kong Clays and Kaolin Co made a formal submission for a 20 year lease.

A site survey was arranged to identify the area for the mine and a new mining licence for ten years was drawn up and issued in January 1961, backdated to 1st August 1960. A number of comments were made, including the request to allow manufacturing on the site, as Mr McBain proposed to build a tile factory on the site. This complicated matters, as the Mining Ordinance did not provide for such a development and a private treaty grant would be required.

By February 1964 the lease had still not been issued and now Jardine Matheson Ltd were interested in taking over the site. Details are rather sketchy but it would seem Jardine purchased Hong Kong Clays & Kaolin Co Ltd along with a ten-year licence starting in 1970. As reported in the law case ‘Ko Ming Dan and Another v Ko Kwok Kue and Others’, January 1998[xvi]:

In 1978, Mr. Ko acquired H.K. Clays from a Mr. Wu Won-hoi who in turn had acquired it from Jardine Matheson Ltd. Mr. Wu sold this company because kaolin extraction was uneconomic without blasting and he did not have the resources for blasting operations. Further, the mining lease was due to expire in 1980. In 1983, K.K. Ko who was by then running H.K. Clays persuaded the Government to renew the mining lease. H.K. Clays was given a ten year mining lease, back-dated to 1980 upon payment of a premium of $6.3m. At the same time, H.K. Clays agreed to build a tile factory on an adjacent site. The factory was completed at the end of 1986 and production on a trial basis began in 1987. The factory and its machinery was financed partly by bank borrowing and partly by shareholder loans from Mr. Ko.

H.K. Clays did not flourish during the 1980’s. It never paid a dividend. Apart from 1988, when it made a small profit of some $485,000.00, it operated at a loss. By 31st December 1989, it had an accumulated deficit of $13.2m. In the following year, there was a net loss of $5.4m and the accumulated deficit rose to $18.7m. The company’s total liabilities were $49.5m including a bank loan of $15.5m and shareholders loans of $20.7m which came principally from Mr. Ko.

Events had, however, conspired against H.K. Clays. Its main competitors in the tile industry were from Italy, Taiwan and Spain. In the late 1980’s, there had been a sharp fall in the value of the Italian lire, so that Italian products had become much cheaper. The business environment for H.K. Clays’ products was very bad.

The mining and tile factory leases were extended until July 1996 when the Director of Lands informed the company that they would not be extended[xvii]. The site was then rezoned in 1998 for development with work commencing in 2021 for occupation from 2029[xviii].

Mining Process

The white clay is found in bands from a metre to tens of metres deep between layers of overburden a few metres thick.

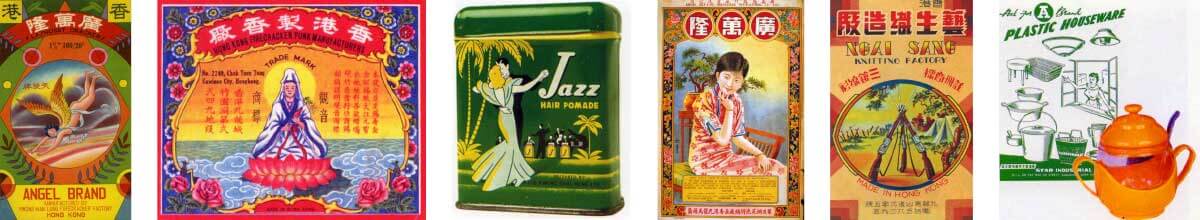

With the removal of the overburden, the clay was extracted by hand before being manually sorted into different grades. These were then dried and the highest quality material was selected to be processed by washing. This process produced a highly plastic kaolin rich in alumina, ideal for pottery. The majority of the clay after drying was sold locally for ceramics, bricks, rubber and as a filler in cosmetics, while the bulk of the processed kaolin was exported to Japan where it was used as a filler for rubber and cloth.

The best material was subjected to an onsite processing to remove quartz and to reduce the felspar, thereby improving the quality and selling price. This was achieved by:

- Grading the kaolin by its fineness and colour, the best being mixed with water until the clay dissolves into a colloidal form.

- This colloid water was then drained through a series of sieves into small channels with the clay solution being deposited in tanks.

- After kaolin was washed and water filtered in the tanks, the clay was dredged up from the tanks to form large loaves and spread on racks to dry.

- Once solid, the clay was removed from racks to an open space where loaves were crumbled into small lumps to be dried under the sun.

- The lumps of dry clay were turned over from time to time to ensure an even texture.

- The dry lumps were then dropped down the main chute to the store houses at the foot of the cliff where the material was graded, bagged and stored for delivery to market.

The price of the clay varied with international supply and demand, in 1947/48 they were selling at $7.72 per ton. By 1958 the rate had increased to $79 per ton and the company was making a profit. However, as the world market for clay increased so did the international competition and they could not compete.

The mine operated for nearly 50 years producing high quality kaolin clay for industry, but like all extraction enterprises it was reliant on the demands of the market and the changing regulatory environment. It was never of sufficient scale to attract significant investment and in the end the site was more valuable for development than production. It was the last of the Hong Kong mining industry.

Images

HKUL Hong Kong Image Database, https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/

Sources

[i] The Historical Comparative Analysis of the Development and Transformation of Lei Yue Mun and Cha Kwo Ling with Their Tin Hau Temples, Chung Fun Steven Hung, 2020

[ii] Report by Mr Stewart Lockhart on the Extension of the Colony of Hongkong, 8 October 1898

[iii] The Historical Comparative Analysis of the Development and Transformation of Lei Yue Mun and Cha Kwo Ling with Their Tin Hau Temples, Chung Fun Steven Hung, 2020

[iv] Hong Kong’s Mineral Deposits, HKRS 545-1-371

[v] Geology of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, P J Strange and R Shaw, Geotechnical Control Office, 1986

[vi] Hong Kong, The Geographic Setting, S G Davis 1949

[vii] The Geology of Hong Kong, S G Davis, 1953

[viii] Geology and Mineral Resources of the Colony of Hong Kong, W L Uglow, 21 April 1926.

[ix] Mining Lot No 11 Application, 18 August 1927, HKRS 58/1/141

[x] Hong Kong, Geological Survey of the Colony, Report on Clays from Certain Districts, 15 May 1929

[xi] Report by the Senior Inspector of Mines, Perak, Federated Malay States on the subject of The Control Measures which the Hong Kong Government Should Adopt in Respect of Local Mining, A E P Kershaw, September 1938.

[xii] Mining Lot No 11 Cha Kwo Ling, HKRS 156/1/856

[xiii] Hong Kong Annual Report 1947

[xiv] Hong Kong Annual Report 1953

[xv] Letter to Superintendent of Mines, from George McBain, 28 May 1954

[xvi] Ko Ming Fan And Another v Ko Kwok Kue And Others, https://vlex.hk/vid/ko-ming-fan-and-845271695

[xvii] Hong Kong Clays And Kaolin Co. Ltd. v The Director Of Lands, https://vlex.hk/vid/hong-kong-clays-and-845345655

[xviii] The Chief Executive’s 2021 Policy Address, https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2021/eng/p89.html

This article was first posted on 16th August 2022.

Related Indhhk articles:

Our Index includes many articles about mines and mining in Hong Kong.