History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 11 – Geological Maps

Tymon Mellor: In the summer of 1920, the Governor of Hong Kong decided that a geological survey should be undertaken of the territory to establish the economic resources of the Colony. The exercise was planned to be completed within 12 months. However, finding suitable personnel and a series of unfortunate events delayed the survey. It was not until 1936 that the first geological map was published and followed much later by the associated report published in 1952.

The First Geological Map

The first ever detailed geological map to be produced worldwide was by an Englishman William Smith, with the publication of his Geological Map of England and Wales in 1815. The map was an accurate reflection of the topography with geological strata information indicated in different colours. Smith also used fossils to assist in the identification of strata in different regions. However, the map was a commercial disaster and ruined Smith. It would not be until 1831 that his work was recognised and the power of the new map was understood. By understanding geology, it was possible to identify possible mineral resources and their commercial opportunities. The story of the map was described in the Simon Winchester book, “The map that changed the world”.

Geological Maps Of China

China has long exploited the available mineral resources with mining activity stretching back at least 3,000 years. Mining technology remained primitive and had changed little until western technology was introduced at the end of the nineteenth century. The mining industry sprung up around local rock outcrops and development was much about trial and error as it was with knowledge and experience. With the influx of western ideas and processes, came individuals with enquiring minds, and one was Thomas William Kingsmill, a British engineer. He was chiefly engaged in exploration and survey work, especially geology[1]. He was based in Shanghai but visited many areas in China. His views on geology were controversial at the time, embracing the idea of shifting polar axis and changes in seas[2].

He was an active member of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society and in 1865 published an article “A Sketch of the Geology of a Portion of Quang-tung Province” including a rudimentary map of the area and its geology[3].

Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society December 1865

Back in Hong Kong, there was little interest in geology, as it was not important to the development of the city until the start of the twentieth century when mineral resources were discovered and exploitation began. It was not until 1906 with the passing of the Mining Ordinance was there a legal framework to allow mineral extraction in the territory.

Early Geological Surveys

Amateur geologists published articles on Hong Kong’s geology, including H B Guppy, a surgeon on HMS Hornet in 1880, who after spending six days exploring Hong Kong Island, produced the first known geological map of Hong Kong Island. The map was hung in City Hall until it was placed in the trust of the University of Hong Kong where it now resides [4].

H B Guppy

With the lease of the New Territories in 1898, Stewart Lockhart undertook a survey of the new lands, and he was assisted by the Director of Public Works, Robert D Ormsby who undertook a geological survey of the new territory. Published as an appendix to the main survey by Lockhart, Ormsby had spent 12 days exploring the new land and documented what he saw, as he noted:

“This geological description of the country is therefore of a very sketchy and imperfect character, and a closer and more careful examination by a professional geologist, or an expert in mineralogy, will doubtless bring to light much that has escaped my observation.”[5]

Others included C M Heanley, Head of the Government Vaccine and Bacteriological Department, and an amateur geologist, assisted by District Officer W Schofield. In 1920 Heanley discovered an ammonite fossil in sedimentary rocks exposed on the northern shore of the Tolo Channel, and this was the first discovery of Mesozoic fossils in southeast Asia. He also had time to produce two geological maps of parts of the territory.

The First Hong Kong Geological Map

With mineral resources being identified within the territory, the Governor, Sir Reginald Edward Stubbs, agreed that a geological survey may be required[6] to ascertain the economic resources of the Colony. The Governor contacted the Director of the Geological Survey of India, Dr E H Pascoe to see if he would offer the services of an officer for the task. The response was negative as the Survey of India was already understaffed and unable to meet its own needs. Pascoe did suggest however:

“If you desire to obtain the services of a geologist at once I would advise your advertising in paper like Nature, The Spectator, Athenaem, Geological Magazine and arrange that applicant for the post should be interviewed by a geologist of repute”

In May 1921, the Governor wrote to the new Secretary for State for the Colonies, a Mr Winston Churchill, advising that a post of geologist will be created with a salary of £800 per annum for the one year necessary for the survey[7]. On receiving the letter, Churchill asked the Imperial Mineral Resource Bureau for any recommendations for a geologist that may be interested in the assignment. In December 1921, it responded with a proposal from Professor Brock, the Dean of the University of British Columbia.

Proposal from Professor Brock (1921)

The proposal from Brock was to undertake the geological survey over several winter seasons, with one faculty member in Hong Kong each year, minimising the disruption to the University. Brock proposed three specialists: Dr S J Schofield in physical and structural geology, Dr M Y Williams in palaeontology and stratigraphical, and Dr W L Uglow in mineralogy and petrography along with his expertise in reconnaissance and economic geology.

The Brock proposal was recommended to Churchill and during 1922 discussions commenced on the details of the survey. This included, the need for an accurate topographic map and the scale to be adopting for the geological map. The survey was forecast to require three seasons of field work along with the support of “an intelligent local man”. The plan was to send his “best field man” Dr Schofield in the first year to establish the scale of the work and the basic geology.

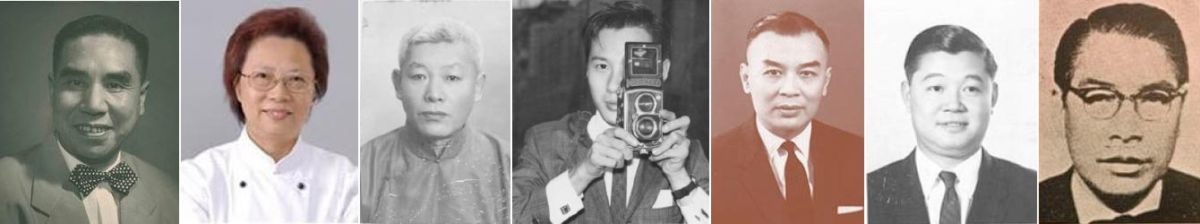

Professor Brock, Dr Schofield, Dr Williams and Dr Uglow

By January 1923 Brock and his team were appointed and arrangements were made for the survey to commence in September, 1923. Dr Schofield the ‘best field man we have in Canada’ spent six months in the territory, establishing the main sequence and succession of the rocks. For the winter season of 1924, Dr Williams followed, and then by Dr Uglow in 1925. Dr Brock spent the winter season in Hong King in 1926 and 1932, the latter visit to update the field mapping. At the start of the study, the team had been provided with a copy of the 2” Newland map, but this proved to be extremely inaccurate. By 1932, the new 1:20,000 map (GSGS 3868) prepared by Wace was available. All the field notes were transferred to the new map set[8].

While in Hong Kong, Dr Uglow had time to prepare a paper, “Geology and Mineral Resources of the Colony of Hong Kong”, published in April 1926[9]. His findings were not positive with regard to “metalliferous deposits” or valuable metals noting that “Small deposits containing lead, silver, zinc, copper, tungsten and molybdenum minerals occur in several places, but no one place are they yet known to occur in sufficient quantity to warrant economic mining”.

He was however, more positive about the availability of materials for bricks and building stone. Given the problems of water shortages in the territory, he touched on the possibilities of artesian water suppliers, possible small quantities in the Shau Tau Kok valley and Castle Peak area. He also warned of the risk of hillside construction and the need for heavy foundations to avoid collapses such as the Po Hing Fong collapse of 17 July 1925 when a retaining wall collapsed after heavy rain resulting in 75 deaths.

Extract from Brocks Papers (UBC Archives)

The University of British Columbia has a several boxes of documents, notebooks and maps from the original 1924 survey. Above is an extract from one of the maps showing how the territory was divided into areas. It is not clear what criteria was used for the area identification as it does not seem to match topography. The base maps is the Tate map from 1904 but updated with the Kowloon Canton Railway, opening in 1910, suggesting a second revision was printed or this had been marked up.

With the survey complete, the resulting geological map of Hong Kong and the New Territories was prepared. The geological information had been recorded on the 24 1:20,000 map sheets and these were sent to London to be reduced in scale to 1:84,480 to match the existing three quarters of an inch to one mile, GSGS 1393 map of the territory. The topographic map had originally been published in 1905 based on the Tate and King maps and updated in 1932. The map with the geological overlays was published by the Ordinance Survey in 1936 with a print run of 350 copies[10]. The team now needed to finish compiling their notes and publish the geological report to complete the assignment.

Geological Survey of Hong Kong (1936)

However, misfortune had already began to waylay the team, delaying the preparation and publication of the associated memoir. In 1926, Dr Uglow returning to Vancouver, met with a fatal accident in Honolulu and was never able to discuss his findings with the team. In July, 1935 Dr Brock, before completing his section of the report died in a plane crash in British Columbia, leaving Dr Schofield and Dr Williams to the complete the report. Their draft was sent to Hong Kong in 1939 while Dr Schofield died in 1943 from a mysterious tropical disease, leaving the only surviving member of the team, Dr Williams.

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, many documents and in particular maps disappeared, and the post war speculation was that the documents were considered to be of strategic value, as S G Davis of The University of Hong Kong noted in 1947:

“I have a feeling that the great value of the maps [there were 80 copies in the CSO library] must have been fully realised by the Japanese (they were never for sale at the book shops) and it is likely that they were sent to Japan”[11]

In addition to the loss of the Geological maps in Hong Kong, Davis reported that the original plates for the 1:84,480 had been destroyed by German bombing of Southampton and only one known copy of the map was in existence located at the War Office.

In an attempt to locate the 80 copies possibly removed by the Japanese, a claim for ‘restitution of looted property’ was submitted for the 1:20,000 working set and the 1:84,480 printed set was made in the summer of 1948. After extensive investigations in Japan, in September 1948 the military confirmed that the documents were not in Japan and advised[12]:

“All documents, maps and records were reported as being burned at the termination of the war, and if the subject property was ever in Japan it is believed that it may be been included in the number so destroyed.”

While waiting to see if any documents could be found in Japan, Dr Williams, the last surviving member was asked if he could prepare a new report from the information available. Despite the 25 years gap since the start of the study the new report was completed in the autumn of 1948 and submitted to the Hong Kong Government. Dr S G Davis was asked to review the report prior to publication. After reading the manuscript twice, Dr Davis was of the opinion it should not be published. There were several mistakes, errors, missing information, superfluous information and the section on economic geology no longer reflected the mining activity in Hong Kong.

The Geology of Hong Kong (1952)

Back in London, a committee had been formed in February 1944 to consider the need of colonial geology. The committee recommended a survey of the Empire be undertaken to identify mineral resources that could be exploited for the greater good, led by the Imperial Institute of Mineral Resources Advisory Council[13]. In June 1948 Dr F Dixey, Director of Overseas Geological Surveys for the Colonial Office visited the territory to understand the local situation regarding mineral resources and water supply. Dr Davis took him around, and as the paper reported, they spent a day “exploring mines in bandit-infested territory on the Chinese frontier. He was guarded by an armed police escort, yet despite such precautions some anxiety was felt for his welfare in Lin Ma Hang, which he visited and where the silver and lead mine owned by Hongkong Mines is situated, is probably the most dangerous area in the New Territories”[14].

In July 1948, Dr Dixey presented his report on the territory. In his two days visit, he was briefed on the situation and paid a visit to a number of sites. He was satisfied with the available topographic and geological mapping and recommended re-printing the surviving copy of the 1936 geological map. He recommended a more detailed survey be undertaking into the extent of the mineral deposits in the New Territories. He suggested that an experienced geologist be employed to undertake a field survey and review the available records. He considered that suitably experienced geologists were employed by the Malayan Geological Survey and that they may be able to spare someone for the September 1950 to May 1951 period to undertake the survey[15].

The Location of Minerals from The Geology of Hong Kong (1952)

Dr Davis proposed to the Hong Kong Government in October 1948 to go to Canada to visit Dr Williams and work with him to clean up the manuscript, and he considered five or six months should be sufficient to complete the task. On the 5th August 1949 Dr Davis took the SS Java Mail to Canada to meet up with the remaining team that had prepared the original report. In addition to spending time with Dr Williams to clear up major concerns, he was able to locate the original notes and field maps. He also managed to find slide copies of the 1:20,000 geological maps that had been deposited in the University of British Colombia library. He also identified that Miss Bottger, Dr Brock’s former secretary responsible for the typing and editing of the original report, had never been paid for her work. A $500 Canadian dollar honorarium for her was duly arranged on Dr Davis’s return to Hong Kong, paid by the Government. With all the background information now at hand, Dr Davis took to editing and re-arranging the manuscript. He was able to include more recent findings and added chapters on Economic Geology and Archaeology. Following a final consultation with Dr Williams in Vancouver the memoir was published in July 1952.

While Dr Davis was completing the Memoir and map, back in London new plates were made from the surviving geological map and 500 copied were printed in 1950 and a further 1000 copies in 1955.

As for Dr Dixey who recommended the geological survey, there was no money or suitably qualified personnel to undertake the task. As the Director of Public Works, J J Robson noted in 1962, “if I had to choose between having a geologist or an additional civil engineer, I would favour the latter”[16]. Hong Kong had bigger problems: a rapidly growing population, water and housing shortages, the need for new infrastructure and housing, all within an unstable region. Mineral extraction was not a priority.

Sources:

- Kingsmill, Thomas W, https://whowaswho-indology.info/3492/kingsmill-thomas-william/ ↑

- The Geology of the Asiatic Loess, Nature, 10 Nov 1892 ↑

- http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/misc/jras_new_2_1865.shtml ↑

- The Work Of The Hong Kong Geological Survey, R J SEWELL, K C NG, C W LEE & C F WONG, Aug 2008 ↑

- Report on the Geology of the New Territory By Mr Ormsby, October 1998 ↑

- Letter Governor to Secretary of State for the Colonies, 13 July 1920, CO129/467 ↑

- Letter Governor to Secretary of State for the Colonies, 26 May 1921, CO129/467 ↑

- The Geology of Hong Kong, S G Davis, 1952 ↑

- Geology And Mineral Resources Of The Colony Of Hongkong BY W L UGLOW MA MS PH D︱ ↑

- Wartime Geotechnical Maps, Ted Rose, The Geological Society ↑

- Geological Survey File, S G Davis, 10 Apr 1947, HKRS41-1-1835 ↑

- Memorandum from Patrick H Tansey, Brig Gen, USA to Chairman, UK Reparations and Restitution Delegation , 21 Sep 1948 ↑

- Geological Survey of the Colonial Empire, 5th Dec 1949, HKRS 41-1-5416 ↑

- Colony’s Water, Geologist’s Survey, SCMP 27 Jun 1948 ↑

- Geological Survey, Dr Dixey’s Report, SCMP, 1 Jul 1948 ↑

- Geological Survey, Director of Public Works to Commissioner of Mines, 2 Apr 1962, HKRS 934-3-39

This article was first posted on 3rd September 2024.

Related Indhhk articles:

- Mapping Hong Kong Part 1 – Where Are We?

- Mapping of Hong Kong Part 2 – 1841 The Belcher Map

- Mapping of Hong Kong Part 3 – 1845 The Collinson Map

- Mapping of Hong Kong Part 4 – 1866 Map of San On District

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 5 – Mapping Kowloon

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 6 – 1901 The Tate Map

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 7 – 1904 The Maps of King and Newland

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 8 – HMS Pegasus

- History of Mapping Hong Kong Part 9 – The GSGS 3868 Map

- Mapping Hong Kong Part 10 – The 1963 Hunting Survey